I am sorry for the couple of weeks delay in publishing the continuation of this series. It was caused at least in part by my collarbone* and in part by just how difficult the next two posts have been to write.

In this series I have shown that the biggest source of losses (actually realised) so far at Fannie and Freddie have been private label securities (notably senior tranches of subprime and alt-a securitisations). The traditional business (insuring well secured and well documented qualifying mortgages ) has caused very few losses thus far (though substantial provisions have been taken).

The dross in other words was in the private label securities.

Now I stated in Part II that whilst Fannie and Freddie have made their biggest losses in private label securities they happen (perhaps by dint of better underwriting) to have the better end of the worst part of the mortgage market. The next couple of posts aim to explore that statement and measure it against the provisions which Fannie (and particularly Freddie) have taken thus far. I am conducting a robustness check on Part II and hence a check on the robustness of the starting balance sheet used in the model presented in Part VI.

Fannie’s statements about better underwriting of private label securities

Fannie Mae has publicly argued that whilst they have losses on private label mortgage securities their losses are far less severe than market. I have not done the work on individual securitisations at Fannie Mae to back that statement – but I will reproduce a graph from Fannie’s credit supplement comparing Fannie owned Alt-A private label securities with market private label securities.

Note that the cumulative defaults of the pools on which Fannie Mae owns the AAA strips are running just under half the cumulative defaults of the market average Alt-A securitisation.

They appear to have this better result without huge differences in the indicators by which they have selected the loans. From the same page in the supplement here is a comparison of Fannie Alt-A credit characteristics with market Alt-A credit characteristics.

The biggest difference is that they did fewer adjustable rate and negative amortizing loans – that is they purchased fewer loans with payment shock (when payments reset).

I do not have any real analysis of how Fannie managed to pick Alt-A loans that were so much better than the market. I would welcome informed comment. But the obvious place to look is at Fannies’ relationship with Indy Mac. Fannie had a close (and costly) relationship with Indy Mac – and the above data suggests that Fannie was allowed to cherry-pick Indy Mac’s book.

That said, the close relationship between Fannie Mae and Indy Mac (which seemingly allowed cherry-picking of Indy Mac’s book) did not give Fannie good mortgages, just a better calibre of dross.

Freddie Mac’s better than average class of dross

Fannie claim to have better-than-average Alt-A private label securities. Their mark-to-market provisions have however been lower than Freddie Mac – and I have not compared individual securitisations to Fannie’s marks as reported in their accounts.

I have made that comparison for Freddie Mac. Freddie Mac has taken very large marks in their accounts for private label securities (and by the end of the first quarter of 2008 Freddie had reported larger losses than Fannie based primarily on these marks).

Freddie do however have a (legitimate) claim for better-than-average selection of (bad) AAA subprime securitisations. There will be write-backs based on this.

Let me however introduce you to the Long Beach Mortgage 2006-11 (subprime) securitisation.

Long Beach Mortgage was the subprime mortgage company associated with Washington Mutual. The loans were way too risky to put on Washington Mutual’s balance sheet – and the performance of these loans is many times as bad as the performance of Washington Mutual’s own balance sheet.

Moreover, the later securitisations were done in the subprime bubble the worse they performed. Pools that were originated late in 2006 (such as 2006-11) behave considerably worse than pools that were originated even as late as early 2006. There is a reason for this. If you were a borrower who borrowed in 2005 and you could not repay your mortgage in 2006 you did not default. Instead you simply took another mortgage (often taking cash out on refinance) and repaid the old mortgages. Early 2004 and 2005 pools showed few losses for some time even though the underwriting standards were atrocious. The reason was that the bad loans rolled into later securitisations. The cynics (correctly) observed that “a rolling loan gathers no loss”. The late 2006 pools are truly atrocious because they contain not only the bad loans originated in late 2006 but also refinances of the bad loans originated in 2004 and 2005. The ability to refinance a bad loan just ended – with the result that the late 2006 vintage is especially atrocious.

So when we look at subprime mortgages originated by Long Beach Mortgage in late 2006 we are looking at amongst the worst credit originated during the whole bubble.

Freddie Mac took a large exposure ($408 million I gather) to AAA strips backed by this appalling pool of mortgages. They will lose money on that – and have taken provision. But surprisingly they will not lose quite as much as you would at first glance think – because - despite playing in the sewer - Freddie Mac took some measures to ensure that they could at least keep their nose above the sludge.

You will find the original offering documents for the 2006-11 series here. Much of the rest of this post is dependent on unusual features in those offering documents. So here goes.

Most mortgage securitisations (or credit card securitisations or the like) had a single pool of mortgages (or credit cards) and tranched them into many strips (often 15 or more). Credit defaults were attributed to each strip in order. So if there were a small number of defaults junior tranches (originally rated maybe BB) would wear those defaults. If there were more defaults mezzanine tranches (often originally rated A) would bear those defaults. Only if there were very large defaults would the senior tranches (originally rated AAA) suffer.

Often AAA tranches had 15 percent of protection – meaning losses had to be 15 percent of original outstanding before the senior tranches lost a penny. It was argued that it was inconceivable that say 30 percent of mortgages in a pool would default. And it was inconceivable that the loss given default (severity) would be more than 50 percent – so (it was argued) it was doubly inconceivable that there would be enough losses to affect the AAA securitisations.

Alas we now know that to be false. Many AAA strips are seriously impaired as defaults and severity have been substantially higher than what was considered even conceivable just a few years ago.

The long beach securitisation(s) look just like this except for one thing. Instead of having one underlying pool of mortgages they have two underlying pools – Group 1 and Group 2. These individually support their own AAA strips but collectively support mezzanine and junior strips. Now this strange structure was done for a reason – the reason being that the GSEs (notably Freddie Mac) wanted to ensure that they had more protection than the average subprime pool investor. These loans were real dross – but they wanted the better end of the dross. This is explained in the (2006-11) prospectus.

The trust will acquire a pool of first and second lien, adjustable-rate and fixed-rate residential mortgage loans which will be divided into two loan groups, Loan Group I and Loan Group II. Loan Group I will consist of first and second lien, adjustable-rate and fixed-rate mortgage loans with principal balances that conform to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loan limits and Loan Group II will consist of first and second lien, adjustable-rate and fixed-rate mortgage loans with principal balances that may or may not conform to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac loan limits.

Now don’t think the loans in Group 1 conform to Freddie’s normal loan standards. They do not. But they are better than the Group 2 loans. We know this in a couple of ways – the most important is that the average original principal balance for the Group 1 loans is $185,000 versus $273,000 for the Group 2 loans. Also the concentration in California is lower for group 1 loans (28 percent versus 54 percent).

Now I started this with a (hyper bullish) view that whilst the Mezzanine strips of various loans might be trashed, the Group 1 loans – being pre-selected might be OK even though the Group 2 loans (the publicly traded high rated parts of the securitisation) might be very bad. Alas that is not the case. Indeed the surviving Group 1 loans are very bad (though not as bad as the Group 2 loans).

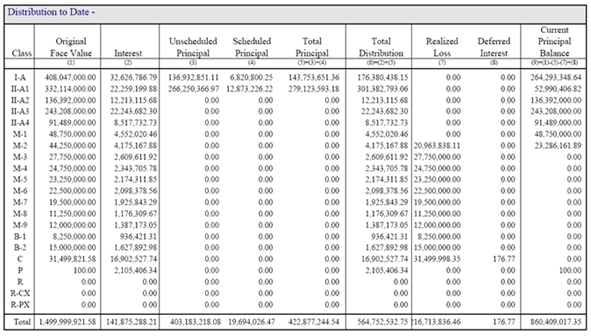

Anyway here is the cumulative distributions and realized losses for the various tranches of the 2006-11 securitisation – these distributions and losses covering both groups of loans. Note that this is a very-late-cycle securitisation and would have high expected losses as a percent of original outstanding…

This data comes from a Deutsche Bank (as trustee) monthly statement to holders of securitisation paper. You can find the trustee report here…

The way to read this is that the mezzanine strips have been almost entirely wiped out – and the losses are coming very close to imposing on the senior strips. For example the M4 strip had an original face-value of $24.75 million. That is how much investors paid for that interest in the mortgage pool. They have on that investment received $2.344 million in interest but their principal has now been wiped out. They are gone – and there is no recovery. However so far the losses have not been big enough to actually reduce the principal owing to the A strips. The 1A strip (which I gather is owned by Freddie Mac and is backed by the better mortgages) was originally just over $408.0 million. They have received all interest owning, 6.8 million of scheduled principal repayments and $143.8 million of unscheduled principal. The are still owed $264.3 million of the 408 million invested. On the money they have received back (in cash) they can take no losses – the money is in the bank.

The collected Group 2A strips originally invested (332.1+136.4+243.2+91.5=) 803.2 million of which ( 53.0+136.4+243.2+91.5= ) 524.1 million remains outstanding…

We also know how many loans were originally in each group and how many remain from this table…

And now we see the big advantage of Group 1 over Group 2. Group 1 has 326.2 million in loans outstanding backing 264.3 million in Group 1A certificates outstanding. Group 1 can absorb mortgage losses of $61.9 million before Freddie Mac (as the AAA strip owner) loses a penny.

By contrast Group 2 has 534.2 million of principal balance outstanding supporting 524.1 million in AAA strips. They can only lose a further 10.1 million before the AAA takes cash losses.

The better-than-pool collateral backing the Group 1 certificates has helped Freddie Mac because even now – with huge losses already incurred – Freddie has taken no cash losses and still has 23 percent excess collateral. They still have considerable protection.

I was hoping to stop this post just here - but

Note that Freddie still has considerable extra collateral backing their exposure to one of the junkiest pools in the whole subprime mortgage bubble. I was hoping that excess collateral was enough – and that Freddie might – through dint of clever structures and preselecting the best loans in a pile of dross be able to get through the whole subprime thing with only mark-to-market losses that would soon reverse. In other words I was hoping for a hyper-bullish reversal of most of the losses discussed in Part II of this series…

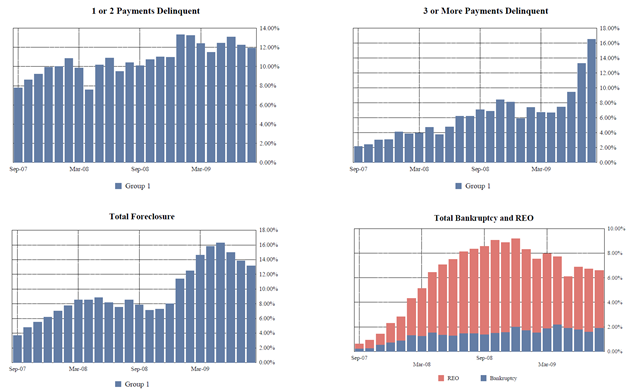

Alas the remaining loans are truly atrocious and 23 percent excess collateral is not enough. I know it is unlikely to most readers to assume you could pick a bunch of loans have more than 50 percent default and 50 percent loss given default – something that would be necessary to impair Freddie’s Group 1 AAA certificates. But – this is a late 2006 Long Beach securitisation. Unlikely as it might have seemed just a few years ago the losses will be much worse than that. Here is the delinquency data for the Group 1 loans.

This delinquency is almost 20 times as high as Freddie Mac’s conventional (non-credit enhanced) mortgage book. Different pools of mortgages can have a delinquency and default difference by a factor of 20 depending on underwriting – and unfortunately the underwriting at Long Beach mortgage was bad – even for the Group 1 loans (which were pre-selected to be better).

There is 12 percent (and flat) early stage delinquency, 16 percent (and rising) late stage delinquency, 13 percent (and falling) foreclosure and 6 percent (and flat) bankruptcy and REO. That is 47 percent problematic loans.

I have only educated guesses as to how many of these will eventually default – but an upper end assumption is that end default should be 1.2 times current delinquency. Not all the early stage delinquents will default of course – but there will be new delinquency and some non-delinquent loans will eventually default. Anyway a reasonable (though high-end) guess is that 56 percent of outstanding principal will eventually default.

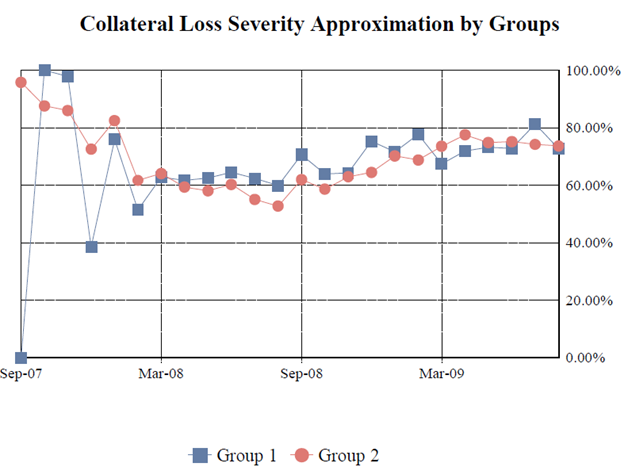

Still 56 percent default would not impair us dramatically if loss severity were only 50 percent. After all we still have considerable excess collateral left on this loan pool before the AAA securitisation tranches are impaired. Unfortunately severity is running MUCH higher than 50 percent. Here is the severity for both the Group 1 and Group 2 loans.

Note severity is running about 75 percent. That is implausibly high and suggests very bad loan servicing. [The severity data is the subject of the next post.]

Still this suggests that the end loss from the Group 1 pool to come is very high – 56 percent default and 75 percent severity – suggesting 42 percent of the remaining pool will be lost.

I am not going to go through this but it is substantially worse for the Group 2 loans (the ones Freddie rejected). The delinquency for Group 2 loans is even higher.

What this means for Freddie

Remember above I showed that there were 326.2 million in Group 1 left outstanding. We think the loss on this will be 42 percent or 137.0 million. There is however 61.9 million in excess collateral protecting the AAA certificates. That will all be lost and 75.1 million in losses (137.0-61.9) will be visited on Freddie Mac.

Freddie Mac has a $264.3 million outstanding balance – they will lose (75.1/264.3=) 28.4 percent of the outstanding balance. The structure protected them – Group 2 loans will have much bigger losses – but losing 28.4 percent of the outstanding balance is still atrocious. Its a better class of dross.

Generalising the 2006-11 series

I have fiddled with a lot of Freddie Mac securitisations in the course of writing this series. As a rule Freddie securitisations had structural features which meant that Freddie Mac losses were smaller than market losses but are large nonetheless.

However the 2006-11 series is a particularly bad series (subprime, late in the boom). Most series have losses for Freddie below 25 percent of outstanding balances remaining as of June 30. Any mark worse than that and they are going to write back the excess over time.

Here are the marks as reported in the last 10Q:

Note the amortised cost of the subprime exposure is 63.9 billion and the gross unrealised loss is 24 billion. That is a 37.5 percent mark. After careful looking through securitisations I cannot find a single securitisation where I think Freddie will lose above 30 percent – and 25 percent is more common. On that count there is 8 billion which should run back through the accounts as they have marked-to-market and the losses will be not as bad as the market.

The model I presented in Part VI calculated losses and income from the current position of Freddie’s balance sheet. However here we appear to have found another 8 billion improvement on Freddie’s initial balance sheet – that is the real position of Freddie Mac is 8 billion better than I modelled in Part VI.

Freddie Mac reckon that about 10.4 billion of the losses they have booked are “temporary impairment” and should reverse. It is plausible – but my 8 billion is a lower number.

Cumulatively Freddie’s accounts show about 31 billion of temporary impairment – losses that they think will reverse. Outside subprime I have made no effort to test that number – but it seems high to me. Moreover some of this impairment seems to come back through the currently inflated revenue line and I do not want to double count this benefit.

Summary

I noted in Part II that Fannie and Freddie had incurred their major losses to date on their Private Label Securities. However I also asserted that Fannie and Freddie picked private label securities that were better than market – that is confirmed and alas it did not stop them from incurring very large losses.

A careful look at some bad securitisations suggest that those losses are more than full provided for (and hence Freddie in particular is slightly more solvent than this series suggests).

John

*I thank the many people who have wished me well, inquired about my broken collarbone and – in some cases – asked how my treatment fitted in with my analysis of Australian socialised medicine. The short answer is that I am going well. My break is one of the 90 percent that current practice suggests do not require an surgical pinning. So I have put my arm in a sling, taken huge doses of painkillers and waited for the bone to mend. The painkillers are not pleasant. There are lots of side-effects listed on Wikipedia including elation, hallucinations, itchiness, constipation, and excessive sweating. I seem to have all the unpleasant side-effects and none of the pleasant ones. I cannot fathom why people take these drugs recreationally. The painkillers are however better than the pain – which was overwhelming.

I have yet to reduce the painkiller doses – but I am expecting the side-effects to be unpleasant when I do so. I will write this up later for those that are interested – especially how my experience fits in with my views on socialised medicine.