Forgive a long post – but I suspect this might develop into a theme. My business partner thought I should break this post up – but I figured I should put the outline in one place and refer back to it. There may be follow ups but this stands on its own.

My original motivation for this examination was Whitney Tilson's rather convincing looking buy case for Microsoft. Microsoft is – by all conventional measures – pretty darn cheap these days. Whitney Tilson (a well known hedge fund manager) details how cheap and he does so without mentioning what I think is the most important driver.

The driver that I think Whitney was not mentioning – and which I have not quantified – is the shift of much of the world to laptops. In America or Australia if I buy a desktop PC it almost invariably comes pre-loaded with Microsoft. It is however a surprisingly easy thing to do to build your own PC – buying the components separately to get precisely the PC you want. I have done it and works. The reason this is possible is that standards have made the PC modular – all the plugs and protocols are common. Nobody other than serious geeks (or gamers wanting to soup things up) does that in West – but in developing countries it is not uncommon for your local computer supplier to do it. After all – if you put a computer together yourself you do not pay anything to Microsoft – and you can – if you want – you can install a pirated computer system. By contrast. if you go to a computer shop in Mumbai there is a fair chance that the machines are “white label” and the system is “not genuine”. However there is almost nowhere in the world you can buy a (retail) laptop (other than an Apple laptop) which does not come pre-loaded with Microsoft. You used to be able to buy “bare bones” laptops in Australia – where you added your own memory and CPU to your own specs – but I can't find them anywhere.

As the world (particularly the newer markets in India and China) moves to laptops the “not genuine” problem for Microsoft evaporates. Growth in laptops in India is nirvana for Microsoft.

And Microsoft is so cheap that any increase in sales will make the stock look extraordinary. The stock at this point does not need many drivers.

The negatives are the re-emergence of Apple as the “must have” product – especially for the young and affluent and the encroaching of linux – which is now dominant in servers – as well as entering the retail market through things like the $250 net-book computer and through being the basis for some mass market products (ranging from Android phones to PVRs).

I wanted to explore the negatives (especially linux and virtualization) properly and so I spent a couple of weeks turning myself into a geek. This post explores that journey.

If you are a “real geek” and you know what you are doing you are probably going to find all of this shockingly naïve – but I still want your comments because that is how I learn. If however you are like me and pondering the stock maybe I will save you some work.

I will start with a conclusion which should not surprise any geek – but tends to surprise non-geeks: linux is the “real deal” and is a much bigger threat to Microsoft than Apple. However it will also change Apple's (laptop) business model beyond all recognition – and it will do so via virtualization. It will also change the hardware business beyond recognition. Indeed it is already doing so.

I have now changed my laptop to a linux (Ubuntu) machine and run a piece of software (Virtual Box) on it. Virtual Box is a program which pretends it is another computer – a virtual computer. On virtual box I run Windows. This is – I believe – a superior set-up and it is unlikely I will ever run a machine primarily on Microsoft again. I will explain why more fully below – but first I just wish to make a simple observation... if I take the hard drive out of my laptop and install it in my old laptop everything works just fine – the whole computer is functional. If I tried to do that with a windows operating system it would fail. This is likely to be important in the future of computing because I will be able to migrate my computer from a laptop to the cloud – or possibly onto my (linux powered) phone. It is unbelievably useful to have a hardware-independent computer.

I warn in advance that I have not come to very strong stock-conclusions. But I have learnt a lot – so this is a post to detail what I have thought along the way – and an invite to have the “true geeks” correct me.

Three business models for an operating system

There are three business models around for operating systems – two of which are closed source (Apple, Microsoft) and one of which is open source (Linux, FreeBSD etc). The first part of this post explains these models and hence explains what software is good for and what it is not and how that derives from the business model.

Historically the most important of these models is Microsoft. Microsoft builds software which they license very broadly. Anybody is allowed to build a computer and run Microsoft on it. Microsoft sells to almost all computer manufacturers. Hardware makers competed to produce better and faster and cheaper computers. All of that competition took computers from a highly niche product in 1984 to a must-have for a very large part of the world. Microsoft split the benefit of all that competition with their customers and became frighteningly profitable – probably the best business in the history of capitalism.

But Microsoft's willingness to work with any hardware makers is also the big weakness in the system. I have a computer assembled from bits found on Ebay and (sometimes literally) from bits at the side of the road – and it runs Microsoft Vista well enough. It is probably different from any other computer in the world – but Microsoft has to make it run. And that is difficult for Microsoft – and the computers are by-their-nature buggy. This is meant to work with that – but conflicts are rife and sometimes computers have errors for unidentifiable reasons. The reasons are unidentifiable because Microsoft does not release their source code and without that nobody (and I mean literally nobody) can actually work out what went wrong in some instances. Microsoft can – but only because an “error report” gets sent back to them and – provided they get around to your problem – which presumably means provided the problem is widespread – they can issue a patch.

And that roughly explains Microsoft's position in the market... it works for everyone – but it does not work particularly well (though Windows 7 is an improvement). Moreover Microsoft allows you to use cheap hardware – and that is a good thing.

Apple deliberately took a different tack and the company almost failed. However that tack has resulted in Apple’s new resurgence. Apple do not license their software – and so – because they built every computer allowed to use Apple software they know precisely “what is in the box”. Because they know “what is in the box” the machines work. After all – they are not building for 100 thousand different configurations – possibly only the thirty or so configurations that they have sold. And they can test the software on each of those configurations and if it works there they know it works. (They also limit multi-tasking on some devices like the iPhone because multitasking with 100 thousand apps will produce combinations that they cannot possibly have tested.) Less configurations means less complexity. And because of that there is less “bloat” in the system which makes it faster (for any given hardware).

But there is a downside with the Apple model – and the downside is that there is less competition between hardware markers. Competition between hardware makers works for Microsoft far better than it works for Apple and it meant that Macs were always over-priced (even allowing for the fat margins that Apple builds into its hardware). To some extent Apple solved this by moving to x386 (ie Wintel standard) chips – and allowing the Microsoft competition to work for them. This made the machines cheaper but also allowed geeks to load Apple software on non-Apple machines (ie making a “hackintosh”).

This model positioned the Macintosh in the market. It was the computer that “worked better” and was not glitchy – but it was a niche product because it was more expensive.

It was on this comparison that Microsoft rolled over Apple and became the dominant and most powerful computer company in the world. Macs – it seemed – were doomed to be the (darn nice) niche product.

When Apple finally moved to x386 chips the difference in production costs became less stark – but they remained – and they remain to this day. Still – the fact that Apples work means that for many uses the total-cost-of-operation for a business running on Macs is lower than a Wintel setup. I know a medical centre that recently changed and considerably cut costs. Further – and this bears observation – computer hardware is now getting sufficiently cheap that the disadvantage of the Apple model (lack of competition in hardware) is becoming less significant.

It is worth understanding how larger businesses (say 200 plus computers) have dealt with the problems of Microsoft. Essentially they have tried to give Wintel platforms the advantages of Apple platforms via standardization...

What they do is rather than have 200 different computers throughout their business they have maybe one, at most three different models in use at any time. These computers are essentially identical and they have – sitting on the IT guys desk – three exact clones. When new software arrives (say for example a Microsoft update) the software is thoroughly tested on the three clone computers to make sure it produces no glitches. If the software (or hardware upgrade for that matter) causes no problems they roll it out across the network with all the computers being changed when staff power them up in the morning. The system works because the IT specialist controls “what is in the box”. By controlling what is in the box (often restricting the right of staff to load their own software) they get Apple levels of reliability but the ability to buy Wintel priced hardware. They do however pay a price on hardware – which is that they often get tied to exact specifications for computers. If their business expands they can either (a) get a new computer specification in or (b) order more computers under the old specification. When they do the latter (which would be most the time) the hardware maker has leverage – and selling old computers to business at old prices can be surprisingly profitable. [After computers should fall in cost by about a percent per week – so selling an old computer at an old price is a massive winner for the vendor... and is an important part of Hewlett Packard’s business.] Big business – through standardization – are – in this view – trying to emulate the advantage of being Apple.

There is a third model out there – which is the truly open-source model. In open-source the source code for the software is public and so – with appropriate expertise anyone can see what is going on in the software. [This is different from both Microsoft and Apple as their proprietary software makes computers running on them into true “black boxes”.] If you know what is going on in the software you should (again with appropriate expertise) be able to make your hardware work with it. If your hardware causes glitches you can fix it (or fix the drivers) because you can see what is going wrong. The hardware makers have both the means and the incentive to make sure it works. With Microsoft and Apple they have the incentive but not the means (they can't see the source code). So Linux is strangely the best of both worlds – there is competition between hardware makers so it uses cheap hardware and uses it well and it is really stable – as stable as Apple.

There is however a downside – which is that frankly – nobody much has an incentive to make the whole thing work for the end retail user – that is – the user interface has generally sucked. The thing now comes with two user interfaces (Gnome and KDE) and nobody has much standardized anything. Moreover the interfaces are run by committees and – by the standards of open-source products – they are bloated. This downside is rapidly been remedied. A couple of years ago I tried using linux on the desktop (using Mandriva and OpenSuse) and frankly it was not much chop. I now use Ubuntu and it is nice (meaning moderately friendly). The remedy however is slow at coming.

This description places Linux in the market too. The description is (a) stable, (b) able to use any hardware and (c) less-attractive and user-friendly around the interface. This makes it perfect for nerds and geeks who like the stability and like being able to run their peculiar hardware setups and don't care that it requires some expertise. The place where linux found its main home was on servers. Servers are computers that run all the time set up by geeks and let run without much attention. They tend to need to work together. They are perfect for linux. Microsoft has slowly and surely been losing the server market to linux. If you need your server to work really reliably with hardware of various ages it is almost certainly running some form of linux (or maybe FreeBSD another open-source alternative). The Googleplex unsurprisingly runs on linux derivatives as does the space station and probably most nuclear reactors. Its a great system but user-friendliness has always been an issue. [I know that the linux geeks will object to that statement – but it is odd having to learn codes like “sudo apt-get install cinlerra” and discovering it does not work…]

One more thing that linux offers is considerable ambivalence about which hardware you use. You can run it on many kinds of computers. If you take your hard drive out of one computer and install it in another computer it will probably work straight away. Both Apple and Microsoft are very hard-ware specific. This willingness to be used on many computers is a massive help for a system administrator because she can update the hardware and it will work. Compare this to when you buy a new laptop and you need to reload everything on your shiny new machine. Hardware portability is anathema for Microsoft because Microsoft sell new software every time someone buys a new machine. I replaced my laptop because well – my Dell machine was a turd – and Microsoft – bless them – extracted over a hundred dollars from me. I was not replacing the system which was adequate – I was replacing the machine which was inadequate. Hardware independence would have been incredibly valuable to me because there would be much less problem with migrating settings and other painful but essential tasks.

Apple is more comfortable with hardware independence because you are always using Apple hardware into which a massive margin is built. Microsoft make their money selling software – Apple by selling hardware at fat margins. You know this because you can buy an Apple operating system for $40 down at the local shop – and it is a better system than Windows. The only problem is (at least according the end user license*) you are obliged to run this on an Apple machine. Microsoft sell licenses for their system for about 8 times this sum.

The ipod, iphone, Ubuntu, virtualization and other business model changes

There have been several large challenges to the outline I described above. These were not all that predictable – or at least if you predicted them you might have made a fortune on Apple stock. I will deal with them in order.

Firstly Apple have found a niche where their product is simply superior. It is consumer products for non-geeks that want to be (a) super reliable and (b) easy to use. The first of these was the iPod. It was a dead-easy to use music player that met an enormous consumer desire. The previous products in the space (portable CD players, Walkmans) were – at least by the standard of an iPod – very inferior.

The thing about a music player or a phone is that it is ultimately not-that-expensive and it is really important that it just works. And so the Apple model is just superior. And you know this – how would you feel about having Windows on a phone? The question answers itself – there is no reason for a buggy thing (or even a thing with a reputation for bugginess) on a product designed for limited functionality and unsuitable for hardware expansion.

The other non-buggy operating system (linux) is also suitable for phones and Google has done it – the so called Android – which is really a dressed-up version of very-small-linux.

The niche here for Apple however is for products that are resistant to hardware expansion and have to just work. iPads, iPhones and others fit. The completely closed software shop is part of the way to get these things to work. If the software shop is completely closed then you know it won't cause glitches because you control (a) the software and (b) what is in the box.

Windows 7 might be modified for a tablet PC but it is likely you will think about Windows on a tablet just like you think about Windows on a phone? Why bother? A linux limited purpose computer makes more sense – and that is what most netbooks are. The $200 netbook comes with an operating system and some basic software (web browser, word processor, spreadsheet etc) – and with little expectation by the customer that they will dramatically expand their use. A super-stable open-source system is just fine. [You do however attract consumers by allowing games and fun-stuff – and the Apple software shops do that better than an open-source platform.]

The second big change is that the front-end of linux is now becoming more user-friendly. Ubuntu is the big driver here. Ubuntu is a distribution of linux originating in southern Africa with an explicit aim of user-friendliness. Also some of the key products (for instance Open Office) have crossed the threshhold where they are as nice and as functional as the Microsoft equivalent. For most people Ubuntu is a superior operating system to Windows. It is less bloated, does all the key functions and is more stable. Ubuntu has made netbooks at $250 possible – it is a fully functional operating system that will work on a cut-down computer and can be distributed without paying the pound-of-flesh to Microsoft.

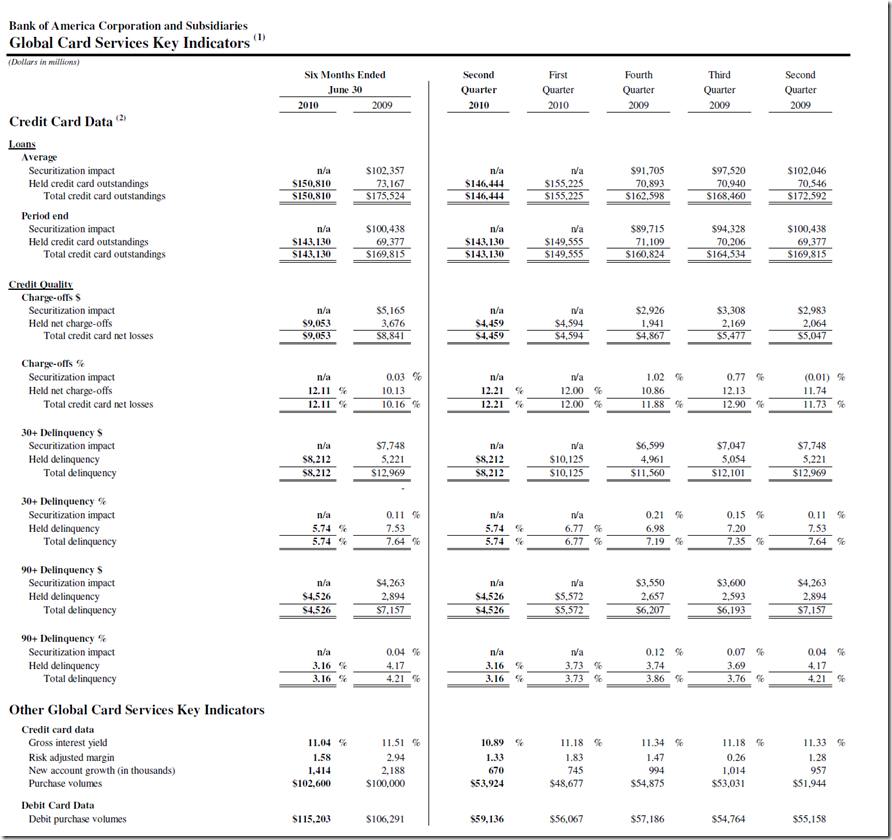

There are however problems. The first is several bits of key software will not run on Ubuntu/Linux. For most consumer uses the show-stopper is iTunes. Apple produces a version for (inferior) Microsoft but will not port it to linux. My guess is that doing so would seriously undercut their own business because – frankly – linux has the stability advantage of Apple at a fraction of the price. From my perspective the difficult programs are Windows Media Player, Windows live writer and my feed reader. There are several open-source products which will play Windows streams. However when the streams become heavily featured (with interactive slides for instance) the open-source players simply fail. I have learnt to hate companies that do their conference calls using proprietary Microsoft systems. [The biggest offender is Bank of America. Will IR please stop it. Pretty please you slime-bag monopolist lovers...]

Still I can't expect Bank of America IR to stop using Microsoft proprietary systems for their conference calls until there is a critical mass of people who complain or cannot listen – and there will not be a critical mass of people who complain until there are enough people who go open source. We have a critical mass problem. You are forced to continue to use the inferior Windows product because – well – everyone uses it. And everyone else uses it for much the same reason. The $250 net-book is a serious threat to Microsoft because it might over time produce the critical mass of people who use Ubuntu or like systems – and that will enable us all (even those of us with pricey laptops) to switch to Ubuntu. [It is a threat that Microsoft is meeting by allowing cheaper operating systems on super-cheap laptops. You can buy a Window 7 laptop in Aldi in Sydney for the same price as a software license. Obviously Microsoft has discounted somewhere…]

There are also other costs of using Ubuntu. The main one simply being that things are different to what you are used to – and hence difficult. For instance you go to the “start” button in XP to turn it off. Who would have guessed that? But you “know” it instinctively. Likewise you know that there is a “snapshot tool” in Vista – but you do not know that the equivalent in Ubuntu/Gnome is “shutter” and you need to download it as it is not standard with the system. We have many years of human capital invested in Windows – and even though it is “inferior” it takes some weeks to change. It is not a light consideration. Inertia is a powerful thing. (Mind you Microsoft faces its own inertia as it tries to move happy-enough XP customers to superior Windows 7. Inertia cuts both ways.)

I strongly suggest you (dear readers) solve the inertia problem for your family and give your 7-10 year old kids old computers loaded with Ubuntu. Relative to anything else you can give them on an old machine it is mondo-powerful – and they will grow up understanding computers in a way that you simply do not if you are not a geek. Open-source is a superior learning environment. [My son loves Ubuntu...] Any school teacher who runs a primary school computer classroom where the computers are not Ubuntu is – frankly – being lazy.

There is a reason why Ubuntu has suddenly got better though – and that there is a rich individual – and more recently Google is behind it. There is an internal Google operating system (not publicly released) called Goobuntu. Security concerns mean that Google staff are now prohibited from using Windows. More pertinently the new (highly minimalist) Google operating system (the Chrome system) is a cut-down version of Ubuntu. Google intends on using Ubuntu and its derivatives to hammer Microsoft – and – frankly – the faster your children learn to use them the better. [The cost for an individual changing is high – I reckon about 4 weeks of productivity – about what it has cost me... but the cost for a child is zero because they have no human capital built into the alternative system.]

There is a third major change to this operating system business – and that is “virtualization”. Virtualization is the business of running a machine within a machine – or for that matter a machine across several machines pretending it is one machine. For instance when you query Google it seems like you are querying one machine – but in reality the Googleplex is maybe a million machines pretending it is one machine. Similarly one machine can be running six to 100 virtual boxes on it. This will fit many of my readers. If you ran a financial business with say 100 staff with their own machine the way you would set it up is with four (powerful) servers – two in the main office – and two mirrored machines in the remote back-up location. Each staff member would have their own “virtual machine” sitting on the paired servers. They would have allocated RAM, processing capacity and hard drive space but when that is not been used it would be allocated to other staff members. Every virtual machine could be made available off-site (for example if staff members travelled). When staff change their desk their machine (which is virtual) does not need to be moved. More to the point – the machine is entirely hardware independent. If you need more RAM collectively you just add it. The servers would be running some flavor of Linux (probably SUSE or Red Hat), the virtual box would be either open-source (“Virtual Box”) or proprietary (VM Ware) and sitting on the virtual box would be Windows or Ubuntu or – for that matter – Macs. [I will discuss virtual Macs later on...] The computer can be migrated from one server to another dead easily [the “hardware” is the virtualization program]. It can be scaled easily. It can be duplicated easily. Moreover the system can be made generally redundant easily (the Googleplex has much built-in redundancy – if a computer or a thousand computers in the Googleplex goes offline it does not much affect the service). VMWare is arguably the hottest stock in the hottest sector at the moment.

The beauty of hardware independence is that everything can be changed – and by running (extremely stable) linux and (unchanging) virtualization programs you can bring the stability of linux to everything. The virtualization set-up is frankly superior – and it will improve the stability of Microsoft – perhaps eventually to Apple levels.

And that sounds fantastic for Microsoft – but alas it comes with a very big price ticket. Microsoft relies on hardware dependency for sales. The reason I buy a new operating system is that my Dell sucked – not because I really wanted to own Vista (or even Windows 7). I was happy-enough with XP. I had to upgrade simply because – well I had to upgrade my hardware. The motive for buying a new computer is almost never because it runs the latest version of Windows. The motive is that it is a bigger, more powerful computer and my old one can't keep up with my demands (or is defunct as per most Dells). Indeed there is a cost to upgrading. [I hate the new picture-driven menus on Office 2007 – and have reinstalled my old Office 2002 because I am used to it. The upgrade sapped productivity and gave me the incentive to learn Open Office. After all – if I have to learn it all again I should – by rights learn it all again on something that is free and possibly superior...]

Virtualization – and hence hardware independence – will simply mean that Microsoft sells much less. Indeed – I can't see why they need to sell anything at all after they have sold you a virtual seat – you can just upgrade the hardware around your machine and keep the software as pristine as you like. Indeed if the server you use is out there in “the cloud” you will never need anything other than a terminal. Virtualization – and hardware independence – is really scary for the boys from Redmond. [By far the most unconvincing argument in Whitney Tilson’s piece is that Microsoft is a key player in the new trend of virtualization.]

And Microsoft know it too. A while back Microsoft was telling us it wanted to change its model for selling the product to business. Previously they sold it on a one-off license basis. Now they wanted to rent it. And well might they – because with virtualization you might go a very long time between upgrades. They know that consumers (who buy machines rather than seats) would not be interested in that – but maybe they could sucker business along with a lower first-time charge.

Apple and virtualization

This is a harder topic. Apple by-and-large do not sell to “the enterprise” and their computers do not virtualize that easily (primarily because in most countries they will not let you). The Apple End User License Agreement (EULA) makes you agree not to install the software on any non-Apple machine (except in countries where such a restriction is illegal). I think Australia is the most notable “except in” country – which means (I think) I am allowed to install the software on a non-Apple machine. [Third line forcing rules in our antitrust legislation would make it a criminal offence for Apple to enforce their license terms...] Anyway I set up Snow Leopard on Virtual Box – and to tell you the truth – installing it the first time was a first-order pain. However copying it would be easy. [After all – it is virtual and I can copy it very quickly – it is just hardware independent software...] I am going to close it and give my snow-leopard disc as an upgrade to a friend because – frankly – now I run Ubuntu a Mac is simply not that attractive.

Apple don't sell much to “the enterprise” and their model is to sell the software cheap (the system cost me about a tenth of a Microsoft system) and make money on retail sales of hardware. If they can get Apple into big business they win – and they are not savaging their own hardware sales. Apple might get to sell some of their (outrageously expensive) server products to companies that might virtualize. And the given you only need to buy the seat once – and the young customers love their Macs (for good reason) it might actually be the sensible way to run. They might also sell virtual macs through the cloud – at a rental fee.

I suspect however there is another game here. Hardware independence is a truly wonderful thing for mirroring. When I take my Windows hard drive out of my Lenovo and put in the (crappy) Dell it does not work. But my linux disk does. I can set up a mirror for my laptop to a desktop at work (as the same information will work in both places) – so I do not need to cart the laptop with me to and from the office. Given how fast computer processing is getting small and powerful there is a reasonable chance I should be able to clone a whole computer into a mobile phone – and keep it in my pocket – but have it securely running on the desktop as well. Apple could win at this – and I do not want to speculate as to where they are going.

So back to Tilson’s argument

Microsoft clearly is really cheap. And there is a huge driver he has not even talked about – the shift of (say) India from white-label desktops to “genuine Microsoft” laptops. But I suspect the whole business is more vulnerable to a complete paradigm shift (virtualization, cloud etc) than I would like. There is a chance Microsoft’s business just collapses – and with it the hardware business. Hardware independence really is the big deal and whilst I might consider the stock I would not label the holding permanent. The boys from Redmond should be scared because they rode the wave of distributed desktops and laptops to glory and that wave looks a little stale now.

John

PS. In doing this someone suggested to me that if you play a Microsoft Midori (their future virtual offering) disk backwards it asks you to pay homage to the Great Satan. He however suggested it was far more dangerous to play it forward. In that case it might actually install Microsoft Midori.

PPS. Whitney… if you have made it to the end of this then I am saying hello.