I am thinking out loud here – and hope for comments. For our portfolio it has not been a happy few days. You will need to click for the tables.

==============

With a due apology to the Vapors the new bear case for American banking was laid out in recent results (especially Bank of America).

No sex

No drugs

No wine

No women

No fun

No sin

No credit cards

No wonder it’s dark…

I’m turning Japanese

I think I’m turning Japanese…

The second post on this blog (back in the days when I had twenty readers) ran through the financials of a typical regional Japanese bank. I picked 77 Bank (because I once owned it) but I could have picked one of about fifty others. The bank had a great looking deposit franchise off which they made no revenue. After all how do you make any money out of a deposit book when interest rates are zero? It is impossible to make deposit spread. And – in Japan – there was such anemic loan demand that loan spreads had collapsed to near zero. The bank had fabulous credit but remained vulnerable to even the smallest credit downturn because there was no pre-tax, pre-provision earnings to offset the losses against. Anything above the near zero losses would impair capital. This was a nightmare of banking without revenue, without credit losses and entirely without glamour. If you were a shareholder at least you could shrink the bank and return capital (though the Japanese seldom do that). If you were an employee it was worse – all except the very senior employees were paid below what they might have earned had they chosen to be an industrialist rather than a banker – and pay rises were not possible because the banks could not afford them. In America high bank revenue allowed some (very) highly paid employees – but this did not happen in Japan.

I have maintained throughout this blog that I thought that zero interest rates in America would have a different outcome to zero interest rates in Japan because Japanese banks are predominantly deposit franchises and zero interest rates are very bad for them – but that American banks – especially larger American banks – are fundamentally lending franchises and zero interest rates would not impair their ability to make a spread on the loan book. In other words I thought that American regional banks (and super-regionals like Wells and Bank of America) would not become large versions of 77 Bank but instead would return to strong profitability.

This is a deep and fundamental call – and about 25 percent of our portfolio at Bronte is based on this call – so – to put it mildly it matters to us. There are two historic models for post-banking collapse banking sector recoveries. There is the typical model applied in Scandinavia and for that matter in Australia after its last round of banking troubles (1992) but also in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and many other places. That model has the competition wiped out or seriously impaired by the crisis followed by (a) a slow repair of credit impaired balance sheets offset by (b) solid profitability as competition is sharply reduced by the crisis and banking services remain central to the economy. In this model banks either die in the crisis or give you 10 to 20 fold returns from the bottom of the crisis as the surviving banks mop up the (very rich) spoils.

There is an atypical post-crisis banking situation which was Japan. In Japan the banks were always deposit rich (a function of their historic savings culture described in this post) but they became even more deposit rich as customers cash preference increased to hitherto unheard of levels. Loan demand however turned completely anemic – and though competition was somewhat reduced margins were crushed to the point that banks were – at best – marginally viable.

Lots of readers ask me to explain my Bank of America position – especially given I have been so skeptical of their past accounts. The explanation is easy – I have seen this movie before. I looked at the competition a few years ago (essentially a massive shadow banking system outside the majors) and note (with glee) that this low-margin competition is simply no longer there – and as far as I can tell – it is not coming back. I believed that bank revenue would be strong – at least for the survivors – and if you put a five-to-ten-year time horizon hat on. More than that – I thought the revenue – spread over a few years – would be more-than-enough to cancel out the excesses of the last boom. [I expressed that view several times on the blog…]

But there is that other movie. That movie is in Japanese – only the subtitles are in English. A good proportion of my readers are bankers. Dear Readers, you better hope it is not that that movie – because if it is your bonus will be small for the next few years – after which you will negotiate a pay cut. Beyond that your income will go into a bit of a decline. One day some of you will wake up and find that – as a fairly senior banker – you are paid about as much as policeman. Welcome to the middle-and-lower-middle class. In a Japanese scenario bankers are paid less – much much less.

The important thing as a stockholder however is not what next quarter earnings will be (they will be difficult). It is whether – five years from now the surviving American banks are milking their privileged position as survivors or whether the margins have collapsed as-per-Japan making banks horrid businesses.

It is in this context I want to make some comment on recent bank results. I am not interested in whether next quarter will be difficult. I am interested in whether we are “turning Japanese”.

Firstly credit is better than even the most ardent bulls would have predicted at the base of the crisis. If you are still bearish big American banks on credit you either think they are faking it on a grand (even criminal) scale or you believe in a massive double-dip or you are just not looking. Credit is unambiguously improving in the numbers. Most the bears in the financial blogosphere – and there are many – were flat wrong on how long credit would take to turn.

Properly adjusted delinquency is falling (albeit slowly) and charge-offs are falling relatively fast. Charge-offs on mortgage credit at JPMorgan for instance dropped by a third during the quarter. JPM however did state in the conference call that the new lower level of credit losses were flat over the quarter and Jamie D was careful to indicate that you should not extrapolate the falling credit losses into future quarters. That said – even sustainably higher than historic (but not threatening) sustained credit losses should not be a problem because you should be able to price the higher credit loss expectations into loan margins.

Which of course brings us to the bad part of the bank results – revenue. The revenue situation has suddenly got ugly – so much so that it challenges the central basis over which part of our portfolio is organized – which is that we are not replaying the Japanese movie – and that bank revenue will be fine long term just as it has been after most (but not all) banking crises. The trillion dollar question in bank valuation is “are we turning Japanese?” As the Vapors suggested in their classic 1980 track – turning Japanese is no fun (it is also no sex, drugs, wine, women or sin – and in the banking context it is no credit cards).

The market did not like the JPMorgan result and they hated the Bank of America result. The problem is revenue decline – and guidance as per revenue decline. The guidance is simply horrid. BofA is not known for down-beat conference calls – but this was decidedly downbeat. I would love to summarize it – but – hey – but Stephen Rosenman has done so far better than me. Sorry to copy in full – but you can go to the original:

Bank of America's (BAC) conference call is a must read. Warning: it is not for the faint of heart. Its implications for banking, now that Congress has passed credit card and financial reform, are not pretty.

1. The Card Act is expected to cost $1 billion after tax.

2. Regulation E/Overdraft policy changes have already cost $1 billion after tax. The fourth quarter of 2010 will see a further reduction of $2 billion pre tax.

3. The Dodd-Frank Bill impact at this point is uncertain because hundreds of rules need to be written still. It is expected to be very costly.

4. The Durbin Amendment in the Financial Reform Bill is expected to decrease debit card revenue each year by as much as $1.8 to 2.3 billion starting in Q3 2011. BAC expects to take a $7 to $10 billion charge in goodwill in Q3 2010 due to the impairment of the debit card goodwill.

5. Net interest margin is dropping. BAC's dropped 16 bp to 2.77%. Per the call, the low interest environment is flattening the returns banks can get for their borrowed money. Loan demand is weak. As a result, net interest income was down over $800 million from Q1 2010.

These 5 banking nightmares will likely visit other financial institutions. BAC is the first to quantify some of them. BAC reiterates throughout the call that it has no idea how to "mitigate" these. While the legislative action may be intended to help level the playing field for consumers and to prevent banking excesses, for now, it appears to be leveling the financial institutions.

It is surprising that Congress would inflict these new burdens on the banking industry in a fledgling recovery. The idea was to prevent new bubbles from forming. It would be sadly ironic if the reforms were to cause the recovery to fizzle. After all, how many recoveries have occurred without the banks?

Disclosure: No Positions

I read Rosenman’s piece and got bullish. The reason is that 1, 2, 3, and 4 on this list are one-offs. They will compress margin – but they do not lead to sustained margin pressure. That is fine because the bank will – over time – be able to make up the margin elsewhere. As Jamie Dimon might say – if the diner can’t charge for ketchup they might just charge more for the hamburger. They are – if I might put it this way – not Japanese style events. In Japan the bank can’t seem to get away charging for anything.

Alas number 5 on the list is Japan writ-large. Loan demand remained anemic for decades and eventually loan spreads went close to zero. Loan spreads are falling normally – after all older high rate mortgages are refinancing into lower rate mortgages – and I think that will be fine. As long as the competition is not to bad the bank will keep a good margin. Alas some parts of the bank have very bad loan demand.

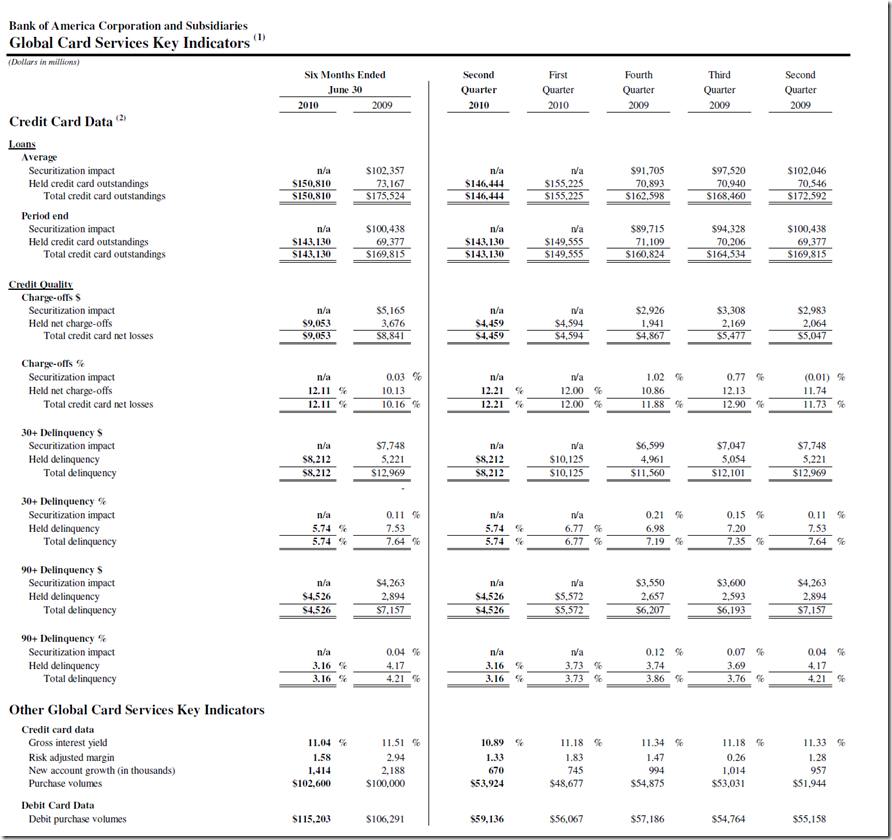

Front-and-center is credit cards. BofA has one of the lowest spread, highest credit quality card books in America. Here is the quarterly data from their cards business. (Remember to click for the full table… and you will need it for the conversation below.)

Now note this is not a junky fee-driven credit card business. The gross interest yield is only 10.9 percent (and falling!). There are still new accounts. But the balances outstanding are now only 143 billion – down from 169 billion. This fall is happening across America. The Federal Reserve data have total revolving consumer credit outstanding falling from 905 to 824 billion in the same period – but BofA is losing share (from 18.7 percent to 17.3 percent). These are the highest spread product on BofAs book. There is no obvious problem with originating new accounts – just maintaining balances. In all of BofA’s results this the “most Japanese” thing you can see.

The rest of the book – well margin is tight – but it does not look to be driven by the things which made Japan so painful for bank shareholders. In the credit card book – not so much.

One thing however leaves me a little chirpier. Purchase volumes actually rose – and they rose well in the quarter. The quarter had almost Christmas purchase volumes. The effect is even more pronounced with debit purchase volumes (ie purchases that do not create a debt). The American consumer did not stop spending – more they just stopped borrowing. I do not know how much of this is people stopping paying their mortgage but still paying their credit card – but there is some evidence that is happening. Perhaps the strongest being JPM’s statement that about half of the JPM second mortgage where the primary mortgage is delinquent are still paying their second mortgage. The same borrowers are also presumably paying off their credit card balance but intend to default on the mortgage.

Finally – and this comes to the competition point – the average yield on this credit card book is sub 11 percent. That is a high interest rate for Bank of America but not a high interest rate for credit cards generally. Despite the tone of the credit conference call (unremittingly bleak as to revenue) I suspect there is a little flexibility to increase pricing in this area. After all the idea of a new securitisation driven credit card originator poaching the business – that seems unlikely. But we will wait and see on that.

Business lending is NOT turning Japanese

Business lending volumes suck. But hey – in non-Japanese fashion the margin on them is actually increasing – it was 2.32 percent verus 2.03 percent a year ago. This is not turning Japanese – it is far more like a conventional post-crisis bank recovery in which margins get fatter.

This does not look anything like a post-crisis Japanese bank – there the margins fell asymptotically to zero.

Finally – what is the long-term downside?

This gives me a little comfort – not much – but comfort in misery nonetheless. Japanese banks have low single digit ROEs. 5% is sort-of-typical. This would suggest that they should trade at very low multiples to book – but they do not. In Japan a 5% ROE is not too bad – because it needs to be compared to a zero percent bond rate – as long as a bank earns more than its cost of capital it should trade above book – and 5% is more than the cost of capital in Japan. So banks with shockingly and sustainably low ROEs trade above book. They might actually a good investment relative to JGBs and you can get outperformance out of misery. BofA is no longer trading far above book. In a Japanese scenario I am not sure you lose to much. But alas you can get really really bored waiting to make no money and misery can last a long time.

For comments please.

John

Post script: since I wrote this Goldies reported – and their revenue was also crunched. So was their allowance for compensation – albeit from very high levels.

21 comments:

The US banks will only go Japanese if long rates continue falling. At 3% on the 10 year, banks will play the carry trade all day to report a decent profit. I think that's the main difference between the US and Japan...the Japanese banks can't even make a spread on JGBs!

I get your macro thesis. It is interesting. It probably has more punch on the bigger names.

For what might be a contrary view, if you ever want to talk to my former employer, Eric Hovde, I would be happy to make the introduction.

https://www.hovdecapital.com

I guess the banks are getting their just deserts. They got their bailout and now they should take their lumps. There is no way hearts should bleed for the likes of Lloyd Blankfein and Jamie Dimon. And, ditto for people who bet on the banks.

so the main driver of this would be extremely low household demand for credit? (as opposed to interest rate spread or credit availability?)

plausible in the short term, but hard to square in the long term with american culture as we know it.

John,

Just to make sure I understand, are you really asking:

For the medium to long term, will the US grow below trend like Japan?

My understanding is the low loan demand in Japan was a consequence of the very slow growth of the Japanese economy. Without economic growth, there were little demand for loans.

I think it is still really hard to argue the US economy will turn Japanese.

Another question I have is:

What are the good investment themes if the US economy does turn Japanese? US Treasury? Chinese banks?

Wow, rarely has a post had so many different sub-topics. In increasing order of importance, I respond -- and feel free to reply offline, you know how:

-You have a key error in your cultural reference. After "no sin" comes not "no credit cards" (your most important line for analogy purposes), but rather "no you."

-MTG reported today, and although they reported their first profit in 3 years, they also said they expect to lose money in 2010, and 2011, and 2012, and 2013 -- because delinquencies get seasonally worse from here, HAMP modifications are basically done, 2005-07 vintage mortgages have "burned out," and (unstated but implicit) housing gets worse again from here.

-On JPM's results, you say "charge-offs are falling." The passive voice is key. An inarguable restatement is "JPM reduced its charge-offs." A slightly less arguable restatement is "JPM reduced its charge-offs even though almost every single macro indicator deteriorated in May-July and housing and CRE face imminent headwinds from, respectively, mortgage resets/recasts and debt maturities (i.e., extend and pretend can't last forever)."

I say everything above as someone who has his fund long BAC. Your core point of "earnings power will overwhelm losses on the old book" is powerful. It is merely a matter of how powerful: "enough" or "hugely"? "Not enough" seems unlikely, because...

On your brilliant dissection of Rosenman's list of #1-4 vs. #5, as in so many cases we are back to _the_ core investing question of the decade: assuming short-term deflation is coming, (a) will the Fed go all-in to stop it, and (b) can they succeed? We continue to think the answer to (a) is "undoubtedly" and to (b) is "probably," i.e. they will do "better" than the Japanese. (That's "better" in terms of deflation, not necessarily in terms of national well being.) The yield curve, bank earnings, and much else ride on the answer.

John,

Do you have any concerns regarding the recent regulatory reform (Dodd-Frank) as follows:

1. will institutional bondholders in major US banks be comfortable with a new wind-down procedure that has no precedent?, and

2. will the removal of systemic support for US banks trigger credit downgrades and increase the cost of funding by the end of the year?

Thanks

A few comments:

-I was concerned about the rising level of repurchase demands from the monolines; which ultimately means FRE & FNM are looking for their pound of flesh for the bank's past sins. This is similar in character to non-performing loans, but isn't on the loan book.

- Credit union competition- see:

https://www.penfed.org/productsAndRates/loans/vehicleLoans/autoLoans.asp?intcid=ad-penfed-specoffers-299AUTOLOANS

a stunningly low rate!

- a friend was pressured by a bank to close his relationships, including a HELOC. He isn't working, but was able to pay it off in full. Banks are behaving unreasonably toward their borrowers.

- On the plus side, on the OZRK call the CEO opined that the next set of lending opportunities would be when commercial real estate loans depart from the structured vehicles they are in to be re-fi'ed back at the banks.

Banks are wont to cry "we'll all be rooned!" whenever someone proposes any regulation, or disclosure. They rarely are.

A lot of the problem will be households deleveraging. This won't go on forever.

When you have committed 25% of the portfolio, I am sure your assessment is spot on as it usually is.

When the loan book shrinks, there is always a chance that the most promising and lower risk borrowers are closed first. So the overall quality of the residual book may not be as good as historical. Of course, if banks continue to generate new loan book it masks the effect. But a minor recessionary headwind may make such a situation unstable.

Best of luck.

One other aspect I was wondering about depositor fickleness risk. What share of deposits would top 10% (or maybe 5% is better) depositors account for?

I don't follow BoA hence these seemingly basic questions crop up. I am sure this is already taken care of.

All best

There are some banks with a surprising proportion of funding in very large deposits - Hudson City (HCBK) springs to mind.

BofA however is the main transaction account for more Americans than any other. I suspect that there are more "franchise deposits" here than in any other place.

======

The issue is not large deposits are hot - although some are. Some deposits are just there because - well - that is where your relationship is...

BofA deposit cost suggests lots of "franchise" deposits.

John

Interesting comments all. I'm in Europe and the picture here is slightly different thanks to the interplay between sovereign yields and short-term ECB money. It seems to me that until Greece/Portugal/Spain actually default it is very hard not to make money playing the curve here. We'll learn more on Friday when the stres tests come out.

Meanwhile I'm fascinated by just how tight pricing on the card book is in the table you've published. I alwasy thought the UK card space was competitive but that's only becuase I hadn't looked to hard at the American space.

I buy into your general thesis (diminished competition leading to outsize returns) but I do wonder what happens before we get there and what the impact of more expensive money will be. It is all very well repricing a book, and a few bips make a huge difference to the bottom line, but the two movies I worry about are the 1970s stagflation vs Japan, not the 1990s Swedish recovery vs Japan.

Surprised with those kind of credit card loss rates you would call BAC a high quality card portfolio. Their loss rates are easily the highest of the six largest CC issuers in the US, and are currently running about 2x AmEx's loss rate. Even (formerly down market) Discover has card losses 400bp - 500bp lower than BofA's card book.

Hi there,

Good analysis. Look, I don't want to throw a wet blanket on everyone...but how can you even think of trusting the numbers these jackasses report? For example, take Bank of America:

Bank of America Incorrectly Classifies $10 Billion of Trades

I mean....they are lying to the SEC and they're not going to jail!

So...my question: How are you hedging against this kind of behavior in your portfolio? That is, how are you insuring yourself against wholesale, outright fraud by the major banks.

Note...I'm not asking as a troll...I'm just curious. I used to spend lots of time reading financials from companies, but the past two years have shown me that you can get burned by assuming that what these people are writing is, in fact, accurate. I've completely lost faith in our corporate / SEC reporting system, and I want to know what's keeping you from losing faith as well (since you're obviously diligently reading this stuff).

I know...this comment borders on flamebait, but I just want to ask the question (since no one else did). I totally understand if you bounce this comment.

For reference, I'm a technical day trader of S&P E-mini futures, and I'm looking forward to everyone's responses! :)

Stephen

In most cycles the curve leads the economy. If the US does head down again, the economy will be leading the curve...flatter.

In contrast to the normal situation, where a steep curve drives Net Interest Margins and also (usually) forecasts stronger economic growth (fees).

Now you get a bizzaro world situation where the curve squeezes margins and, as opposed to the central bank raising rates and thge market pricing in potentially slowing growth, we get the central bank doing nothing and rates falling because the curve is telling you that slowing growth is not a potential but a probable outcome.

Just saying that you can't assume that falling rates are an automatic win for banks.

Thanks for laying out this analysis in such detail, JH. While I would agree with your points on the banks being able to earn their way out of trouble, I remain more worried about the bombs lying around in their trading books--the Bailey Savings and Loan part might be fine, but who knows what lurks in the derivatives part which will overwhelm it?

Regarding BofA's deposits, with an all-in cost of deposit funds of 44 bps in 2Q10, I think we can say that BofA has one of the most attractive deposit franchises anywhere on the planet. That deposit cost of funds is probably in the lowest 2% of all US banks and, consequently, is quite valuable. Now, full disclosure, I'd never invest in BofA because I believe it to be unanalyzable (I doubt even the CEO really understands what's going on down in the bowels of the company), but the value of the bank's deposit franchise is not in question - it's world class.

John,

In your past experience with past bank cycles, how long does it take for balance sheets to start growing again?

I mean, we are so far not long past the recession. It seems reasonable to me for balance sheets at this stage of the recovery to be anemic and even shrinking. People are probably still quite risk averse, and so are banks -- underwriting standards are unusually tight right now.

But the question is, how long does it take to turn that around?

What did you see from the Asian and Scandinavian crises?

Japan banks have had a low interest rate for a long time with a society that has traditional been a saver but look at the Japanese economy at the moment. They have been in a recession for over 10 years.

Having lived in Japan for quite a few years I think people are missing a very important point about whether the US will be "turning Japanese"... simply that is it quite amazing & very Japanese that Japan hasn't had any major social disruption over the past 10-15 years. And I think this a something that needs to be taken into consideration when looking at the US (or even China once their Japan style property bubble bursts) -> there is no way the US will remain stable socially like Japan. If the US can't get itself out of a rut within 5 years everything will become much more bleaker than simply stagnating bank financials...

Post a Comment