A correction to this post re the Australian infrastructure projects is at the end...

The Confidence Game – the book about Bill Ackman’s pursuit of MBIA is a good book – but this post is not a review – rather a commentary ex-post on the whole bond-insurer thing.

For those that do not know financial insurers were a handful of AAA rated companies who guaranteed financial products (mostly municipal and quasi government debt and structured finance) and – through their guarantee – imparted their AAA rating. All of the financial insurers got into some trouble and a few have failed. MBIA somehow soldiers on – Ambac has been split by its insurance regulator. These companies were ground zero of the crisis.

But I will start at the beginning and with an example which is more than a decade old – but which I think explains both the use of and failure of financial guarantors for structured finance.

Imagine a furniture shop which sells furniture both for cash and on store-generated credit. About half the sales are store generated credit and they are known as an easy place to get a loan. Nonetheless the shop has real customers as well – and those customers buy furniture either for cash or on credit cards supplied by third parties. [For those with a keen sense of retailing history I am not thinking of Sears.]

Anyway these loans perform sort-of-ok. The spreads are wide (more than 20 percent) but losses are about 10 percent. The loans are pooled and securitized – and – for the sake of argument – assume a piece of paper is sold entitled to the first 50 percent of the cash flow from the pool of loans. It is pretty hard to see how these loans can fail so badly the senior strip fails to pay.

If even 45 percent of the loans actually pay over the term of the loans (assume two years) then – you will receive back 45 percent plus 20 percent spreads on those loans over two years. That is more than enough to ensure a senior tranche will repay in full. In fact – with a few years of payment history (showing the loans to be good) I would have happily rated a really senior tranche (with 50 percent protection) as AAA.

Ok – but there are things that can go wrong. And – to be really AAA you would need to cover them.

For example – the servicer of the loans can simply fall apart through incompetence or bad management of financial misadventure. So you would – to ensure a AAA rating – want to be allowed to change the servicer. And the deals I saw generally did this.

And – because I am a passive investor I would want someone with some skin in the game to be allowed to change the servicer – so it is useful to have a senior party – perhaps a guarantor – who has both the skill and incentive to change the servicer.

So far this is pretty good – and it is very hard to see why this should not be rated AAA. Indeed if I look at it now – and even knowing what happened – I find it difficult to imagine this defaulting to the AAA level. Sure it would fail in a total collapse of the US economy with unemployment rates above 50 percent everywhere. And I doubt the loans would survive a nuclear war and subsequent nuclear winter. But it is really pretty hard to imagine them defaulting.

But I am cheating. This is a real deal – and whilst nobody was ever criminally prosecuted I have a fair guess what happened. (Civil cases were still running last I looked which was years ago…)

What I think happened was that the furniture retailer made up customers – simply made them up. The people did not exist. The names in the loan files did not correspond to real people at real addresses. Instead the shop “sold” the furniture on credit to imaginary customers and then sold the imaginary loans to Wall Street for real cash. The furniture was then put back on the floor – maintaining the illusion of real furniture shops with real people walking around them.

The securitization trusts had to get bigger and bigger each year – with more fake loans made to make interest and principal payments on old fake loans. When they had grown too large the entire Ponzi came crashing down.

What you saw when you looked at the books was a fast growing furniture shop. When you looked at the shop you saw – well – a shop with real furniture, real staff – a real business.

But what was really there was an elaborate fraud.

The money – hundreds of million – supplied by Wall Street – was never recovered.

Losses in the securitization trusts rapidly went above 60 percent – indeed far above 60 percent.

You see it now – this deal really was super safe provided there was not mass fraud. And mass fraud makes something that looks really quite straightforward spectacularly different from appearance.

----

Flash forward to March 2000 – the height of the tech bubble – and Bob Genader – later to be CEO of Ambac but then the CEO of the Ambac/MBIA joint venture in international financial guarantee was travelling through Sydney. He was underwriting some part of yet another Macquarie deal and he dropped by my old shop for an investor relations meeting. The stock – like many financial stocks – was in the sewer then (memory says it was under $30 which looks great compared to today’s price of about $1 but lousy compared to the $90 plus it traded at later.) This was the first “real company meeting” I had done for my new shop. I started in the business about a month earlier.

Genader chatted with us for about 90 minutes while we puzzled over a business that was 150 plus times levered and never seemed to lose any money. I had done some research for this chat and already knew about MBIA’s AHERF transaction (more on that later) but I was not familiar at all with other parts of the business (for instance I simply did not understand the guaranteed investment contract business which was to cause Ambac so much grief later on).

About ten minutes of the conversation revolved around the above furniture store and the defaulted AAA securities. Genader noted with a smile that no bond insurer covered this paper and observed it must be fraud. He then said something which has stayed with me ever since – he said that

Ambac and MBIA really provided financial fraud insurance. As he described deal-after-deal I had the same impression – I could not see how they could fail – but deal-after-deal could fail the same way – through mass fraud. If the security (say loans or road tunnels or tax liens or whatever) did not exist then the loans would fail.

----

As I looked a little closer there were clusters of deals which could cause major problems without fraud. For instance there were many loans secured by future landing fees at large airports. None of these loans were individually enough to cause Ambac or MBIA problems – but collectively they could be nasty. For instance just imagine if terrorists worked out a truly non-detectable way to blow up commercial planes and did it on a regular basis. They could make

all commercial flight grind to a halt and hence turn

all of the airport deals bad simultaneously. This would make the whole of Ambac or MBIA precarious simply because there were too many airport deals. Risk concentration and leverage meant that even remote possibilities had to be considered to make the judgment Ambac or MBIA were sound. There were just too many out-there things that could go wrong…

I don’t think any of the airport deals have failed – and some that

I thought were questionable are still adequately covered.

Still – I think it was – and remains true that the main thing underwritten by Ambac and MBIA was fraud protection. No fraud meant the deals were OK. Fraud meant that the deals could fail spectacularly. Fraud produced spectacular and highly unexpected losses.

The only underwriting standard that made sense was “zero loss” because any loss 150 times levered could kill you. And the only way to ensure zero loss was to insure only things that could never possibly default and to insure that those deals contained no fraud.

In the furniture store case that would have been easy – get a hold of the loan file and physically check a random 100 loans. Check that the people

really exist – check the sources of payments – check the phone numbers. If anyone had done the fraud would have been caught. Stopping fraud is – at least in the case of Ambac and MBIA – what due diligence was (or at least should have been) all about.

---

Flash back a few years to the 1990s and Sydney’s Eastern Distributor. The ED is part of my life – I drive through it regularly to go to the Northern side of Sydney Harbor (colloquially known as “the Dark Side”). The toll is outrageous.

The ED however required about half a billion dollars of finance. Like all Macquarie deals of the time it required what was then (and is now) a high level of leverage. [This deal was only modestly levered by the standards of 2006.]

This finance was not going to come from Australia as the Australian banks had already had their fill of Macquarie. It had to come from the bond market. There is however only a thinly developed bond market in Sydney. So Macquarie went global.

The only problem was that nobody in the global markets had any idea as to whether the Eastern Distributor was a good deal. If you had asked the what the base traffic level in Southern Cross Drive was they would not have had a clue…

Enter Ambac/MBIA. They could take a piece in the middle of the capital structure. They insured a mid-ranking piece – of about 70 million (and these numbers are from the deep recesses of my memory) about 200 million of debt senior to them and 230 million junior to them.

If the deal with the government was real and the traffic levels on Southern Cross Drive were not faked this piece of debt was money good. It was not going to default – and the risk to Ambac/MBIA was very nearly zero so – by rights Ambac/MBIA should have not been paid much for accepting the risk.

However Ambac/MBIA got paid really well – and they got paid well for a reason. By putting their guarantee (AAA) on an intermediate piece of debt every piece of debt senior to them in the structure was considered (justifiably) by the market to be AAA and the debt that was junior to them was also probably sound. The Ambac/MBIA joint venture – by putting their name to the deal – vouched for the entire deal – and hence improved the pricing of the entire deal. And so they got paid on the entire deal but only insured about 15 percent of it.

I remember working out the ROEs at the Ambac/MBIA leverage levels and assuming high costs – and the ROEs were in the 30s. This was a lovely business – one of the best financial businesses I have ever seen – a Warren Buffett quality business (and it came as no surprise to me that Buffett at various stages had owned some Ambac and MBIA)…

The JV however did have check that there was no fraud. That did not mean they needed to duplicate six months of traffic surveys on Southern Cross Drive – but maybe just five times half an hour check – randomly chosen – to see if the traffic volumes were as presumed in the model were accurate and had not just been “made up”. And I gather Genader made sure that check was done.

The JV was being well paid for ensuring that there was no fraud before it provided a minimal amount of almost zero risk insurance.

A rating agency could come and tell you the debt was AAA – but the JV was

much better than a rating agency. It was a rating agency run by people who looked competent and were risking real money – their own money – on the deal. It was a rating agency that was putting its money where its mouth was. That didn’t mean that they would never get it wrong – but in this case all that was required not to “get it wrong” was to check that there was no fraud – and that was an easy check…

---

Now you see what the features of the “good deal” was. Firstly it was “small” – in this context meaning a $70 million exposure, not a $500 million exposure. Secondly it was a little exotic – and hence by Ambac or MBIA putting their name to it they could convince people that it was money-good. Thirdly people were not buying the deal purely on the rating – they were buying it a little because the JV had warranted part of the deal. Ambac and MBIA’s name improved the pricing of the whole deal – the whole $500 million – and because of that they got a stupendously good ROE for safe projects.

Finally the real risk to this type of deal was “fraud” rather than ordinary credit. Credit risk you “manage” – which is a euphemism for “accept”. Fraud risk however you avoid – and you avoid it by doing due diligence. Due diligence in this case is not hard – but you have to do it – and that means you need a modicum of competence – even if all that involves is sitting a staff member by the highway with a VCR so she can count cars for half an hour on five occasions and hence check the model.

Put this way you can see why Ambac and MBIA deserved to exist – and what good business for them looked like. You can also see why it makes sense to insure things that don’t ever need to be insured because they are “safe”. In reality what they were insuring was a single thing – they were insuring the deals that they insured were not fraudulent. And fraud was not a risk that was accepted and hence subject to cycles – it was a risk that could be avoided altogether through due diligence.

My biggest gripe with the MBIA book is that it does not come to grips with what a “good MBIA” might look like – and what the real reason for MBIA existing might be.

Its only when you put it in that context you see the opposite case – and why eventually MBIA and Ambac really collapsed.

You also see that there is again a case for a new Ambac or a new MBIA – but I will get to that at the end.

---

Crank the clock forward a couple of years. We had invested $60 million in Ambac and had it double. We had invested a smaller amount in MBIA for a much smaller profit – and we had sold both positions because a few deals were making us

mildly uncomfortable. Ambac rose fast just after we sold it and so smug feelings were short lived. (Both positions collapsed much later proving – yet again – that I would prefer be lucky than smart…)

More importantly Bob Genader had been made CEO of Ambac. That was no surprise – the international business had been astoundingly profitable – and the guy who made the money got the job. I spoke many other times Bob Genader usually about individual deals which I did not like. I never traded the stock again until quite late in the collapse and I will be the first to admit I was surprised at how nasty it turned out. I was aware of

individual dodgy deals led by a Conseco securitization but I was surprised just how bad the book was and I was unaware of the so-called “CDO Squared” deals that were spectacularly bad. I had a long standing $10 bet with Genader on the Conseco deal – I thought it would lose money – Genader thought not. It was a bet in good fun…

---

The MBIA book starts with a meeting that Ackman had with Jay Brown – the CEO of MBIA. I too had a meeting with Jay Brown and several of his staff. I was not as well prepared as Ackman – and I was less inclined to be sceptical. That said there was a strange discussion about AHERF which alerted me that all was not quite as it seems – though I only got the full import of the discussion a few years later.

AHERF was a hospital with bonds insured by MBIA that defaulted in the late 1990s. The cost (unimportant the story) was about $200 million. Rather than taking the charge however MBIA agreed to a perverse deal with their reinsurers by which the reinsurers would absorb the charge and recover the money over many years (twenty?) by charging higher premiums in the future. This spread the loss forward rather than taking the charge when the loss was made. The account fakery has a name – it was “finite reinsurance” – the same sort of deal that later caused the AIG-Berkshire problems and landed several General Re staff in prison. It was the sort of deal which induced Jim Chanos to short AIG.

It was legal accounting legerdemain – and was an indication that not all was well…

I asked Jay Brown about it – and there were two things he said. Firstly he said that AHERF was not really a credit loss – it was fraud. The second thing he said was that the finite insurance was set up before he arrived – and

if he had been CEO they would not have done it. The second statement is – I think – actively misleading – but I did not recognize that until later. The first statement – that AHERF was fraud and not reflective of MBIA’s skill as an underwriter however had me in stitches.

I reported Jay Brown’s statement to Bob Genader who raised his glass to Jay Brown – laughed and reminded me again that what they really underwrote was fraud. Brown dismissing AHERF because it was fraud was in effect admitting his company’s failure. Fraud was

always the risk with deals that were otherwise so safe they did not need to be insured.

---

It was the second statement however that should have made me question Jay Brown further. Jay Brown said that if he had been CEO they would not have buried the AHERF loss with finite insurance. This simply does not fit with Jay Brown’s career. Jay made his reputation and fortune with an insurance company called Crum & Forster which had considerable asbestos exposures. It got sold for a good price in part because the buyers did not understand that it was larded with finite reinsurance.

Jay Brown told me with a straight face that he wouldn’t have done it – when – alas – doing that stuff was precisely what he built his career on. Alas that realization came only a few years later.

There were plenty of other instances in the book where Jay Brown’s pronouncements were not to be taken at face value. One stood out – when he was telling the world about the virtues of short-sellers in financial markets whilst getting Eliot Spitzer to investigate short-sellers in his own stock.

But funnily none of what Jay Brown said in the book upsets me as much as when he misled me. As an investor all you need to know whether he is actively misleading but somehow it feels different when it is personal. It takes a certain pathology to look someone in the eye and to tell them what they want to hear rather than the nuanced truth. It is style that makes great salesmen (and Jay Brown is a great salesman). It is also – and unfortunately - surprisingly common amongst the senior executives of Wall Street firms possibly because they got there in part by being great salesmen.

---

Crank the clock forward a few more years and the nature of Ambac and MBIA’s business has changed. Firstly the idea that a toll road in Australia was “exotic” became almost quaint. People were securitizing almost anything and borrowing against the most bizarre assets. When David Bowie securitized his music royalties that was novel. There were however clear and identifiable cash flows and you could see how the finance was going to be repaid. Later – if you looked hard enough – there were plenty of deals where repayment looked problematic.

The international finance business model of Ambac/MBIA in the 1990s – going around the world and giving deals the “good housekeeping seal of approval” had died. Once the JV could guarantee a $70 million piece a toll road in Australia and improve the pricing for the whole $500 million – and thus – through its “good housekeeping seal” it could add value to the whole deal. By 2004 people would buy the toll road debt because Moodys or Standard and Poor rated the deal AAA. Almost nobody cared about rating agency conflict of interest (they were paid to provide the rating). Nobody I knew would have cared that Ambac or MBIA did old-fashioned due-diligence on deals – and ex-post it is clear that they didn’t get their fingers too gritty that way any more either. Standing by the road with a VCR counting cars – well that was passé… as I guess was checking that the taxi driver on the mortgage application did or did not earn 250K per annum.

So rather than doing $70 million deals for relatively large fees Ambac did $500 million deals for smaller fees. MBIA did the same. And they had a few difficulties – notably the Channel Tunnel – but the deal that always caught my eye was the Conseco manufactured housing securitization done by Ambac.

This was a distinctly worse business. They were just selling guarantees they were no longer selling their “good housekeeping seal of approval” and hence improving the pricing of the rest of the capital structure.

---

But something more insidious happened – which was that Ambac and MBIA stopped checking too rigorously for fraud. They must have done some checking because a careful examination shows that many Ambac securitization deals perform better than their non-insured counterparts. But they must have also turned a blind eye in some instances.

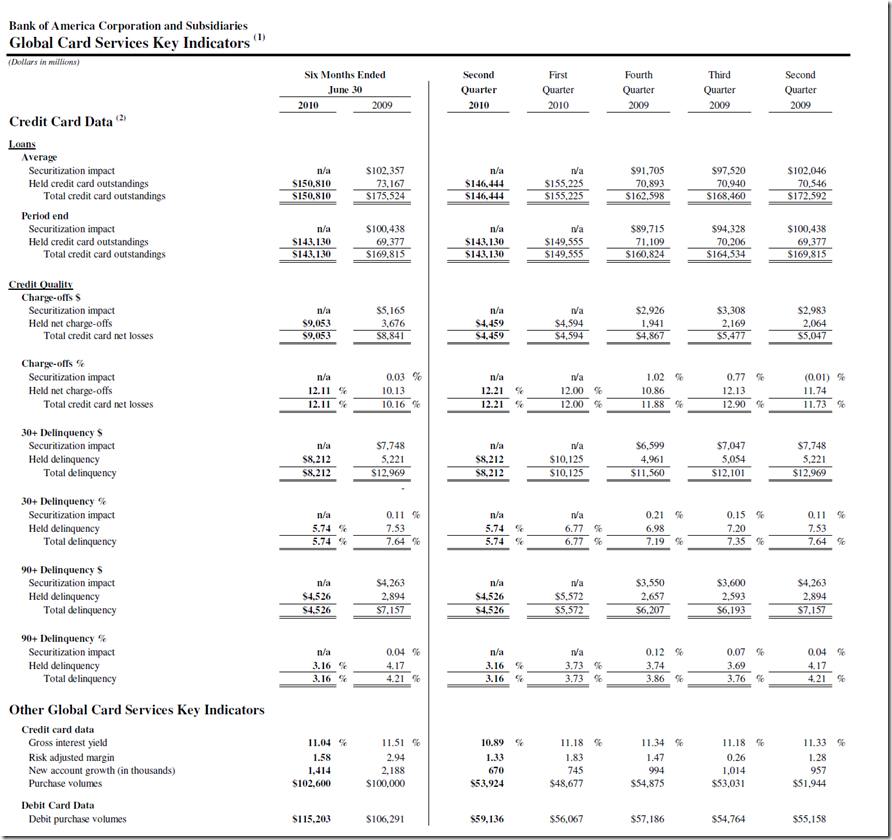

Here is a chart from a presentation by Ambac in 2008 for the net cumulative loss for their worst 12 second lien mortgage securitizations. Almost all their second lien losses came from these deals.

Two deals in particular stand out like sore-thumbs – which are a Bears Stearns deal and a First Franklin deal. First Franklin was owned by Merrill Lynch. These deals had 80 percent loss rates. To get that you need to have more than 80 percent of the loans default because the loans have (small) recoveries and also make some spread. Maybe 85 percent default will do it.

Now it is pretty hard to imagine how you could “randomly” choose 1000 loans and find 850 defaults. In fact I am not sure you could “randomly” do this. Instead you needed a process by which all the bad loans came to you. It probably requires fraud by someone – be it the companies or hundreds of mortgage brokers and thousands of borrowers.

Knowing what Ambac and MBIA really underwrite – which is not credit but fraud – I think you can guess that fraud was a likely cause.

But the fraud was really widespread – these loans have loss rates 20 plus times as bad as Freddie Mac. And the non-guaranteed securitizations – the ones with no fraud check at all – were – on average – far worse than the guaranteed ones.

What really did Ambac and MBIA in is a haze of fraudulent loan origination and fraudulent accounting to hide the problems and fraudulent servicing of the loans and – well – just the ways of Wall Street in a bubble. Ambac and MBIA both failed because they forgot what they really underwrote which was fraud protection. Instead earnest people in their ivory towers (Armonk and the Southern Tip of Manhattan) did mathematical models of loss probability rather than combing though loan files and checking the individuals. The end game of mathematical modeling was CDO squared deals – where the individuals were lost two or even three deep in securitization structures and so there was no way that you were understanding just how corrupt the underlying foundations were.

What was really needed to check the Eastern Distributor was not based on a fraud is easy to state. The main thing was a staff member with a VCR by the side of the road for 4 times half an hour counting cars. What was really needed to underwrite mortgage based securitizations was someone who was someone who would randomly check 100 loans in the loan file making sure taxi-drivers did not self-report their income at $200K per annum. Alas the discipline that saw someone standing by the road counting cars was long-gone. Instead you had management accusing short sellers of fraud rather than management checking whether the loans that they insured were fraudulent.

Ackman’s MBIA short thesis

Bill Ackman’s short on MBIA was a short with an ever-changing thesis. What he saw was a highly levered company – often 140 times or more levered – doing things that were not quite straight. His original observation was the AHERF transaction – something I understood from my first look at MBIA in year 2000. Then he saw one I did not know about – a securitisation of tax liens over properties in Philadelphia. More accurately this was a securitisation of uncollectable tax liens from crack houses and the demolished houses of the dead. The transaction however was rated AAA with MBIA’s guarantee. Moreover MBIA unambiguously knew fraud was going on – firstly there was a tape of a meeting of senior executives in which the truth was on open display – and then there was the name of the transaction – which translated (badly) from the Latin as “black hole”.

The ex-post explanation is (a) these companies underwrote fraud only – as the deals had to be too safe to fail without fraud, (b) they – or at least MBIA – were committing some fraud – some of which was restated, (c) they were turning a blind-eye to fraud, (d) eventually they would be overwhelmed by fraud – in this case fraudulent mortgages – and they would die.

Ackman saw only part of this on the way – but he saw enough of it to simply obsess him. He knew everything that was public to be known about these companies – and he found a lot of bodies and guessed that there would be many more. But he was obsessive from 2002. The companies (MBIA and Ambac as well as the other bond insurers) were not insolvent in 2002 – they were only exhibiting the behaviour that would make them insolvent in the end. His starting position on the companies was almost certainly overstated – they were not insolvent – and – if they retreated to the right business model which was underwriting things that could only fail if they were fraudulent and checking for fraud – then they would have been fine. However the companies themselves reacted to the messenger by accusing him of stock fraud and then – by their own behaviour – dooming themselves to oblivion and irrelevance.*

A plea for new bond insurers

Any decent observer knows the rating agency model is completely riddled with conflicts. Moreover the rating agencies don’t get their fingers dirty – and often explicitly say that they do not check for fraud. I have never heard of a rating agency analyst counting cars for an expressway project. And I have never heard of them going through a loan file and checking 100 random mortgages.

But that is what this is – it is a gritty business. Mathematical models dreamed up by people like me in ivory towers would never have seen the furniture store above for what it was – and never saw the epidemic of truly hopeless loans given out last cycle.

There really are loans that so safe that they can be written with a zero-loss standard and levered 150 times – but they are only that safe if you have removed the possibility of fraud – and you can only really do that by getting your fingers dirty. You cannot do that with a mathematical model.

I am really hoping that one day a new Ambac and MBIA arise – ones that understand their mission – which is to be a rating agency that gets their fingers dirty doing actual due diligence and who have incentives aligned with the bond market. What I want is for the bond insurers to have the vision that Genader once gave me (and promptly forgot). They want to do smaller deals (10-15 percent of outstanding) but improve the pricing on the whole deal. They want to do this with a “good house keeping seal of approval” but not one dreamt up by the public relations firm – but one earned on the ground through loan files and counting cars. I want them to insure only things that can’t fail provided they involve no fraud – and I want them to check that there is no fraud. Because human nature being what it is – we can be assured that the financial markets will one day be infested by waves of fraudulently obtained loans – and if a bond insurer forgets that they go to zero.

One of the downsides of deregulation is “desupervision”. And desupervision is an open invite to scammers, opportunists and the gullible to borrow money they can’t or won’t repay. It is an invite to financial crisis.

Bond insurers at their best are “private supervision of financial markets”. At their worst they are “ground zero for crisis”. And the difference between being a good financial insurer and a bad one? About a decade.

John

*The malefactor company criticising short sellers (“shooting the messenger”) and then doubling up on their ill-deeds is a staple of my trade. Ackman and MBIA provide yet another example.

And now some notes:

1. The Conseco deal was a securitization of all of Conseco’s best manufactured home loans. Ambac insured the whole deal and I suspect the losses will wind up at zero. That looks smart – Ambac got paid well for the deal and took much less risk than it appears. But it is in fact stupid. The Conseco deals done immediately after that deal were truly utterly atrocious. They had a double-dose of bad loans in them. However they sold well because Ambac had vouched for Conseco’s credit worthiness at least at the AAA level. (For the record some of those wound up at Fannie Mae.)

Anyway what Ambac did was sell a bit of their reputation off for money. When what you are really selling is “a good housekeeping seal of approval” that is beyond dumb. It was the behavior in the Conseco deal which made me sell Ambac – not because I thought they would lose money (if they lost money Genader never made good on his $10 bet). It was because they would lose reputation and that would ultimately mean they had to compete with all the other lowlife in financial markets and not make money through adding their seal of approval.

In retrospect Genader should have been fired for the Conseco deal and the cultural shift that it represented. But I did not see it that clearly at the time – and I had too much respect for the man following the super-competent deals he had done as CEO of the JV.

2. Mary Buffett’s book on Warren notes that every Christmas Warren used to give his relatives a $10 thousand share certificate. It was a gift to the limit of the gift duty – but it was also a stock tip – and that stock tip was usually rather good. She has a list of those in the back of her otherwise bad book. Many – notably Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Citigroup, Ambac and MBIA have fallen on hard times. Berkshire/Buffett owned all of those at some stage and none at the end. These were all once good businesses – and they all drifted. The drift happened over a decade or more – you had plenty of time to notice. I noticed the drift at Ambac and got out. But I did not notice how far the drift had gone – and was very surprised at the end. I did not expect Ambac under Genader to get into anything like this much trouble.

3. Bob Genader stopped answering my emails. I would still like another drink and a chat if you are out there…

4. I collect super-smart people as friends. Ackman clearly fits the bill… if he wants to send me an email I would appreciate it.

-----------

Correction: I have my infrastructure project with the middle bit insured wrong. MBIA/AMBAC never insured the Eastern Distributor and it took the middle piece of NO Australian infrastructure project.

The company used to take middle pieces - but stopped doing it because the mantra was "we want the control rights". The control rights are important - the right to take over the project if certain tests are not met. That would allow the company to correct (say) for a bad servicer.

As to Australian infrastructure projects - only one loss was taken - which was the Lane Cove Tunnel. Traffic projections were wrong - probably a wave of people taking real traffic data and making assumptions in their interest (the investment bankers for instance are not paid unless a deal was done.)

Sorry to my readers for the error.

John