The Federal Regulatory Energy Commission (the FERC) is charged – amongst other things – with regulating the rate of return on interstate natural gas pipelines. Rates on these pipelines are by-and-large regulated so as to achieve a targeted return on equity.

Quite of its own volition the FERC has called for a judicial review of on three Midwestern gas pipelines including Natural Gas Pipelines of America (NGPL). In its last rate case (1996), NGPL’s target rate of return was set at 12 percent.

This is a peculiar review because – unlike past reviews – the review was called by the Commission itself and without a complaint from any of the customers using the gas pipeline. [Customers for gas pipelines tend to be large oil and gas companies or large utilities and are usually not shy about calling for a review when rates are out-of-line.]

The FERC has argued – from publicly available documents – that the returns on the NGPL are (just) over 24 percent – and hence (and these are their words) are “unjust and unreasonable”. They use lots of emotive language and have petitioned a judicial review to get the rates cut. You can find the full document here. A good press summary is here.

To put it bluntly the FERC stuffed up. It simply got the math wrong because it does not understand rates of return and depreciation – a staggering oversight for a body charged with regulating pipelines. Worse – on the math presented – the rates on the NGPL should be increased in order to allow for the FERC mandated 12 percent return.

This is a pretty nasty allegation – so I need to explain the basic mathematics of regulated returns. I will start with the simplest of models that I can.

The simplest pipeline model

Imagine a pipeline that cost $100 to build. It lasts 2 years. The regulators have to allow the pipeline to recover an amount (say $x per year) so that the present value of $x per year adds up to $100.

Now $x has to be more than $50. Why? Because over 2 years the pipeline has to recover at least the $100 that it cost to construct. Depreciation alone is $50 per year – and having the pipeline recover only $50 per year would mean it made no profit.

We could (naively) presume that because $100 is employed the pipeline needs to make $12 per year profit in order to get 12 percent return. So we would set $x at $62. That unfortunately gives us a little too much return – because – in the second year the pipeline only has $50 of capital employed (they have recovered $50 through depreciation). You can do the math here (and you assume for simplification that the cash is all received at year end) then the $62 received after year one would be worth $55.36 discounted at 12 percent and the $62 received in year 2 would be worth $49.43. Add those up and you get more than $100.

I used the “goal seek” function on Excel to work out the required annual return on the pipeline under the simplifying assumption that the annual payment is received in two equal increments. I have linked the original spreadsheet (to convince you that I have done this correctly).

In this case note that the required cash flow each period is $59.17c. You can discount this if you want by 1/1.12 in the first year (getting $52.80) and by that squared in the second year ($47.17) and lo – these numbers add up to $100.

Now here is the clinch – which is that we know – by initial assumption here – that the return on equity for this project over its life is exactly twelve percent.

But what is the return on average equity in the second year?

Return on average equity in the second year!

The cash return in the second year is $59.17 cents. [It needs to be that every year to provide a 12 percent return on equity over the life of the project.] The pipeline depreciates by $50 per year over its two year life. So the measured profit during the second year is $9.17 (the return less depreciation).

Capital employed commenced the second year at $50 (being the cost less the $50 of accumulated depreciation). It ended the second year at $0 – as the whole pipeline had been written off by then. The average capital employed for the second year is thus $25. Given the stated profit is $9.17 the return on average equity for the second year – as recorded – will be 36.7 percent.

This return will be observed even though the return on the project over its life is only 12 percent.

There is nothing sinister about an observed 36.7 percent – and more generally there is nothing “unjust and unreasonable” in the observed returns of 24 percent of the Natural Gas Pipeline of America. These returns are simply a mathematical artefact of the allowed return on equity of 12 percent over the life of the pipeline. The observed ROE of 24 percent does not warrant a rate case – it is as to be expected. Indeed as the pipeline in question is more than half depreciated I would have been surprised if the observed ROE was below 24 percent – and the 24 percent ROE does not represent a problem or a failure of regulation.

What we have here is a regulator who has failed to understand the basic math of the business which they are meant to be mathematically regulating.

The deskilling of American regulators

I am no longer surprised at the general deskilling of American regulators. This post demonstrates that the regulator – whose job it is to regulate the rate of return on gas pipelines – has no idea at all of the basic high school mathematical implications of that regulation. I am used to SEC officials who can’t read a balance sheet or can’t see the Madoff fraud when it is laid out in front of them. But the rot spreads more widely. We have bank regulators who were blind or stupid and now we have utility regulators who can’t do basic math.

A more generalised formula for what should be the observed returns on a pipeline

Warning – seriously wonky – here I do the math to show what the observed ROE should be. You don’t need to read this – just accept the regulator has their math shockingly wrong. But here is a way of working out precisely how wrong!

Being a nerd I thought I would help the regulator out with their math – and indeed it is not too hard to derive a generalised formula for the right observed return on a pipeline. But hey – why bother when Wikipedia does it for you? Wikipedia gives the present value of a stream of n paymnets of value A as follows:

PV(A) is the present value of the stream of payments – which in this case should be the construction cost of the pipeline.

i is the rate of return – which in the case of FERC should be the regulated rate of return (12 percent), and

A is the annual cash return on the project, and

n is the number of years over which the project receives its return (which should be the depreciable life of the pipeline – or in the above example 12 percent).

Now I would never use a formula out of Wikipedia without checking it (which I did by derivation) but for my readers I thought I should just plug in the above example – where the cost of the pipeline is $100, the annual payment is $59.17, i is the usual 12 percent and n is two years. Plug the following into your calculator – it checks out just fine:

Now we can rearrange this standard formula to determine A:

Now we can also work out what the year-end capital employed (E) in year j of n is. That is trivial – it is

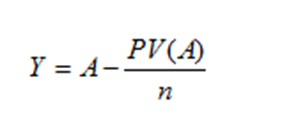

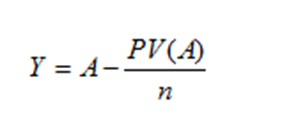

Income in any year (Y) is equal to the annual payment less than depreciation. In the formula below I just assume that the original cost of the pipeline depreciates in a straight line over n years.

Now the FERC is really obsessed by the observed return on equity on the pipeline (in this case about 24 percent). But lets work out what the observed return on equity should equal:

You can rearrange and simplify this equation any way you like – I can’t really be bothered – I am lazy. But hey we now have enough to work out what the observed rate of return should be. Assume that the initial cost of the pipeline is 1 (it would cancel from top and bottom of the above formula). The depreciation in the FERC document for the pipeline is 50 years – so n is 50. The pipeline originally cost $3.728 billion but has accumulated depreciation of $2.273 billion – so we are in 35 of 50 – so in the above formula j is 35. We are going to allow the regulated rate of return – which is 12% – so i is 0.12. Plug this in and we get the following:

Just to check that I am not wrong I have done the same in a spreadsheet – which I have linked here. But the lesson is that the observed rate of return should be 33.47 percent even though the project actually only returns 12 percent over the life of the project.

An observed rate of return on 24 percent – the rate that FERC is complaining about – is too low.

FERC is right of course – the tariffs on these gas pipelines are “unjust and unreasonable” – they unjust and unreasonably low. On FERC’s own numbers they are not adequate to provide the lifetime 12 percent return on equity that FERC mandates.

What are the options here?

I guess the easiest options for the owners of the pipelines are to allow the FERC numbers as to depreciation and capital employed to go to the judge uncontested. They do not seem out-of-kilt with reality. They then should present the math straight (and there are plenty of mathematicians who will do a better job than me) and they should ask for a rate increase!

I do not think the judge will have any problem giving it to them. But it is not the public policy objective here – and we wound up in this spot because of the mathematical incompetence of the FERC. It is time to stop the rot at the FERC.

Stopping the rot at FERC

And it should stop relatively quickly. Barrack Obama appears to have appointed a competent man to be the head of the FERC. Whilst Jon Wellinghoff may have spent most of his career as an attorney he has – according to his CV – an undergraduate degree in mathematics (University of Nevada 1971). He should be more than capable of checking the math in this post.

I have contacted his office and given him a copy of this post. Jon Wellinghoff endorsed and press released the review of the rates for the various gas pipelines. He is however more than capable of withdrawing his request for a review. Indeed I think he has to before the FERC is made a laughing stock as the SEC was after Madoff.

I will happily announce when he has reacted appropriately.

John

PS. The pipelines who would have had their returns slashed under this review include Northern Natural – which is owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway. I have not received or asked for a consulting fee but Berkshire holders (many of whom are my readers) should be sending their thanks...

PPS. I am serious about the deskilling of US regulators. I have spent only a few hours thinking about the mathematics and accounting of rate of return regulation in my life – and I spotted and roughly quantified this error within five minutes. Regulators who do this all day every day should simply not make mistakes like this.