Whether the Spanish banks are hiding their losses is a major debate going on in the blogosphere and has been detailed at length in the Financial Times. The stakes are very high – this is a debate about the stability of the Eurozone and possibly of Europe itself.

Background

I have a lot of American readers whose interest in finance stops at the American border. I need to outline what is going on.

Spain had a monstrous building boom – a building boom on (at least) Californian standards based very much on coastal development. The building boom has slowed considerably. The building boom attracted relatively unskilled labour – as building booms are apt to do – and about 40 percent of all migrants to EU settled in Spain. Wikipedia (I wish I could read the original Spanish source) state that the foreign population in Spain has gone from about half a percent of the population in 1981 to over 11 percent recently. This change in racial mix has resulted in only minor tensions (with the possible exception of the large terrorist attack in Madrid).

The financial crisis has hit Spain hard. Unemployment is about 20 percent – though this overstates the GDP contraction. A lot of the new immigrants are now unemployed.

Twenty percent unemployment would normally result in large bank losses – indeed you would expect bank insolvencies. However this has not happened. The two giant Spanish banks (Santander and BBVA) appear amongst the most profitable in the world and have substantial market capitalisation. Strangely Spain looks solvent despite its apparent economic catastrophe. Part of the explanation might be that the economic problems in Spain fall mainly on the newer immigrants and the unskilled end of the labour market – and that these people are not the loan customers of the bank. In this formulation the Spanish recession is about the same depth as the American recession – and the 20 percent unemployment rate is just an artefact of the migrant economy.

Either way both big banks are depleting loan reserves (at least compared to delinquency and non-performing loans). But both banks are reporting low losses and low loan arrears.

The banks however could be lying.

The stakes are enormous. The bears (led by Spanish resident Economics Professor Ed Hugh and the financial research house Variant Perception) argue that the Spanish regulators and banks are conspiring to hide Spain’s insolvency – and when Spain turns out like Argentina either the European central bank (that is the old German central bank) will bail out Spain at great cost to the Central Europeans or the European monetary experiment – and possibly the whole European political experiment will be challenged as Spain fails economically and socially. It’s alright to bail out Latvia after its economic disaster. Latvia is small. Spain however is large and important in a European context. Ed Hugh would argue that it is best to deal with the problem now – because delayed it will get much worse.

Do not for a minute think that the stakes here are overstated. Full blown economic collapses (eg Latvia, Iceland, Argentina) usually lead to riots and governments falling. Where ethnic tensions run high those riots often have a racial element (rioting crowds find scapegoats). Europe can paper over the Bronze Solider riots in Estonia (which pre-date the crisis). They can paper over riots in Iceland and Latvia because the economies are small. But an economic disaster in Spain would pose major difficulties – difficulties I think European Union would survive – but which would stress the system to its core.

To be this bad though the banks would need to be hiding their losses on a grand scale. Most banks in crises hide a few losses (and spread them over time). However the bears are truly apocalyptic. The Variant Perception report is an absolute classic of hyper-bearishness. If it really is that bad then either central European taxpayers are going to be stuck with a huge bill or the core political union in Europe is vulnerable.

Less worried folk have pointed to inconsistencies in both Ed Hugh and Variant Perception’s data analysis. An ordinary level bank failure could be dealt with by Central European taxpayers with only minor stress – however if you believe Variant Perception we are not looking at an ordinary level collapse – its way bigger than that. Ibex Salad – a blog with the unlikely topics of the Spanish Stock Market, Spanish Economy and the olive oil business is the counterpoint to Ed Hugh and Variant Perception.

The data is mostly ambiguous – as the bears would argue – the data is largely faked anyway – finding inconsistencies in the data is to be expected. They would argue that common sense – and the overbuild visible when you open your eyes – indicates that there is a serious problem here.

I really do not know. I am not close enough to the ground in Spain to know – and – frankly – analysing (supposedly) faked data in a language I can’t read from a desk in Australia is unusually difficult. But there seem to be four variants.

(a). The Spanish banks are telling the truth – and this is a storm in a teacup,

(b). The Spanish banks are doing a normal amount of bank over-optimism in the face of a crisis – and whilst the banks are really stretched (but not telling us) the banks are ultimately solvent – and the European experiment is fine,

(c). The Spanish banks are in fact diabolical – and the losses are maybe 15-20 percent of a year of Spanish GDP – in which case a bailout by (effectively) German taxpayers is possible or

(d). Variant Perception is in fact unreasonably bullish – and Spain will collapse economically and socially and we will be thankful if all we get back is someone like the Generalissimo. The modern European experiment will be deemed to fail because a single European Union with a single currency can’t hold together in a crisis because Germany won’t or can’t bail out Spain, Italy and Greece in a crisis.

Instinctively I am in camp (b) above. However I acknowledge all of the above are possibilities.

Migration, racism and currency union

I am going to do a little further explaining of the stakes here. The threat to currency union in Europe always was ultimately racism.

When you have currency union you can no longer have a high interest rate in Spain or Italy (when those economies warrant a high rate) and have a low rate in Germany when Germany is recessed. You have a single interest rate across the currency zone.

The underlying state of most of the past 15 years was Spain booming, Germany mildly recessed. Currency shifts or shifts in value between the Deutsche Mark and the Peseta can – by dint of currency union – no longer happen. The main mechanism of economic adjustment is removed.

America has always done that. The same interest rate applies in the rust belt, in the sun belt, in California and in Boston. And we know how economic adjustment happens. Americans move. A vast number of Americans do not live in their home town and the bulk of the world’s busiest airports are American. Internal American migration is massive.

However migration within Europe has always involved more issues. The languages are different. Several countries have histories of nasty endemic racism. There are large cultural barriers.

Monetary Union – whether by design or just outcome was always going to confront those barriers. And it was always going to be slow. There is a reason why the German/Spanish imbalance was so long lasting last decade – which was that it is much harder for a German to move to Spain than it is for say a Hoosier to move to California.

The changing racial mix of Spain throughout the boom seemed to show that massive shifts in racial mix and massive internal migration could be accommodated without the tensions of Europe’s dark past. They were the embodiment and a proof of the European political experiment. If Spain collapses beyond bail-out (as per Argentina) then monetary union is over – and economic union with racial harmony will be challenged.

As I said – the stability of Spain is a big issue and the crux point is the losses in the Spanish banking system.

The Spanish American data

Sitting at my desk in Bondi Australia I have no real advantage in answering the big questions about the solvency of Spain and whether Spain really is the black hole in Europe’s balance sheet.

But I can add to the debate. The Spanish banks have American operations – and using reasonable comparisons we can work out whether the Spanish banks are hiding their American losses. So far I have not seen any analyst do this – but it is surely worthwhile. I am going to focus on BBVA because I once had a detailed understanding of their American operation (Compass).

Several years ago BBVA paid a premium to buy Compass to form BBVA Compass.* This is how they describe the bank:

BBVA Compass is a leading U.S. banking franchise located in the Sunbelt region. BBVA Compass is among the top 25 largest banks in the U.S. based on deposit market share and ranks as the third largest bank in Alabama and the fourth largest bank in Texas. Headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama, it operates 579 branches throughout Texas, Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Colorado and New Mexico

This bank files US statutory filings (better known as “call reports”). There is no reason to presume that the Spanish regulator is conspiring with American regulators to fake the accounts of a bank headquartered in Alabama. Moreover there are other sunbelt banks to use as comparisons – whereas in Spain you can only really compare BBVA to Santander – and the bears would argue that there is no point checking for faked data by comparing it to other faked data.

If BBVA is telling the truth in America then there is a reasonable chance they have a culture of truth telling. That would suggest that they are probably telling the truth in Spain.

However if BBVA’s American accounts are riddled with deception (or at least an overly-optimistic prediction as to their losses) then it is likely that BBVA has a culture of understating losses – and that that culture extends home to Spain.

Of course the truth could be (and I would normally expect the truth to be) somewhere in the middle. A little bit of excessive optimism is normal behaviour for a banker in a crisis. But a little bit of excessive optimism does not imply bank or national insolvency – just some difficulty. The European experiment can survive that.

So what does the BBVA Compass call report say? Is BBVA hiding its American losses? If so – how bad loss hiding culture.

I have posted the key Call Report to Scribd.

Here is a a comparison – comparing BBVA USA ratios to a sample of similar bank holding companies chosen by the FFIEC. (You will need to click for the complete picture with all three tables in this post.)

The instant conclusion is that BBVA has higher delinquencies than the competition but has lower loan loss provisions and is charging less off than the competition. This conclusion is robust almost no matter how you cut the BBVA USA data. I think we can safely conclude that BBVA is hiding its losses. If anything it is slightly worse than the above indicates because nobody in their right mind thinks that the comparables (larger American regional bank holding companies) are honestly stating their losses. But if the comparables are understating losses then BBVA is understating them more.

This puts me firmly into camps (b), (c) or (d) above. The question is no longer whether they are hiding the losses – but whether the scale of problems (in Spain) is sufficient to cause major political ructions or whether it is just an issue for the stock market. [Disclosure: I am short BBVA and the position is modestly painful as the stocks have appreciated.]

How are BBVA hiding their losses in America?

There is a time honoured way of hiding losses in banking – a method that Variant Perception suggests is being done on a breathtaking scale in Spain. The method is rather than call a bad loan bad – to just extend it a bit more credit. If the borrower can’t pay the interest give them a bigger loan or line of credit. They will use the loan to become current. The slogan is that a “rolling loan gathers no loss”. Even the most diabolical subprime mortgage book in the US showed only small losses until the market stopped rolling the loans.

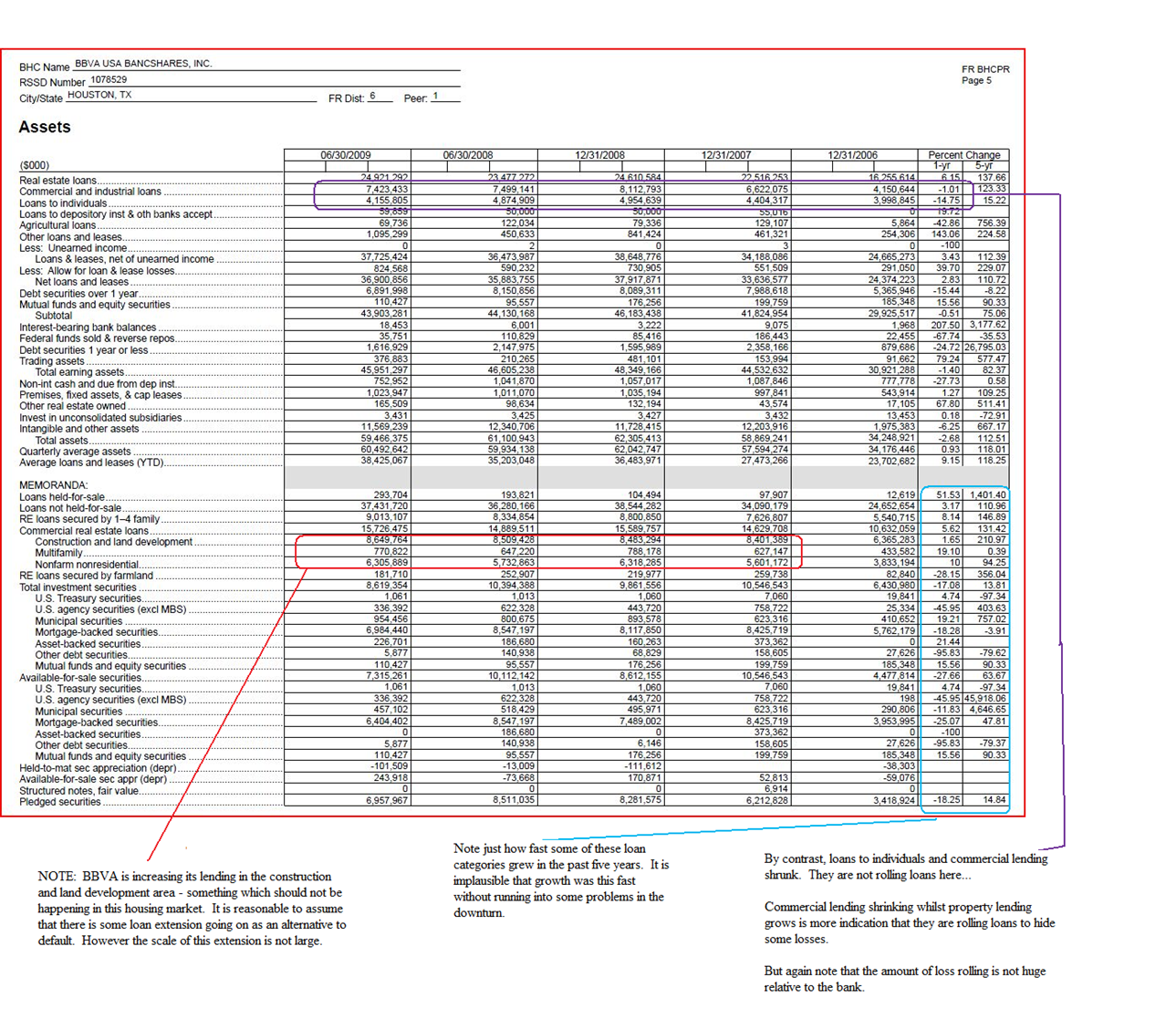

We have some evidence that BBVA is rolling bad loans. Here is the loans outstanding by sector (again you will need to click for detail):

The level of rolling loans is not at the alarming levels that Variant Perception alleges are present in the Spanish economy. Then again Alabama and the other states in which Compass is large do not have 20 percent unemployment. The aggression which BBVA grew the book in the past five years however is breathtaking. You can see where all that Spanish risk comes from and why Spain had such a monstrous property boom.

Construction loans – a perspective from the American book…

The main allegation in the Variant Perception report is that the Spanish banks are massively overweight construction loans – and that they are extending those loans rather than allowing default. The core statistic is given in the following paragraph:

Consider this: the value of outstanding loans to Spanish developers has gone from just €33.5 billion in 2000 to €318 billion in 2008, a rise of 850% in 8 years. If you add in construction sector debts, the overall value of outstanding loans to developers and construction companies rises to €470 billion. That's almost 50% of Spanish GDP.

They add that they think that most of those loans will go bad (which implies a Spanish crisis many times worse than America – and implied bailout requirements that are similarly bad).

Construction loans at almost 50 percent of GDP is a truly astonishing figure. The entire US mortgage market is roughly 10.4 trillion dollars – or about 75 percent of GDP (and as the crisis has shown that seems too large). The idea that construction loans are nearly 50 percent of GDP had me falling off my chair. I tried to confirm this figure (as it felt like garbage). Alas I could not. However Iberian Securities has done some legwork:

Variant picks-up a classic wild-card to spice-up the report. Specifically, they say most of the €470bn in outstanding loans to developers/construction (50% of Spain’s GDP) could go bad. The report forgets to mention- however- that a chunk of the €32 bn in outstanding loans to developers does not necessarily involve residential lending but commercial lending (which is relatively safe in Spain , in our view). It does not say either that a not-low percentage of construction activity in Spain involves public works, so a proportion of the construction-related debt (€141bn) should be attached to that public sector accordingly. Also it is worth considering that residential work-in-progress in Spain — one of the biggest contributors to the €320bn figure — is generally collateralized (with Spanish major developers reporting LTV of 50-65% approx). Factor-in these and the final loss on this portfolio should be a fraction of what Variant claims. In our models, we assume a 15% peak NPL ratio on Developers (7.6% in 1Q09) and a 10% NPL ratio on Construction loans (6.7% in 1 09).

Even at 6.7 percent of GDP construction loans are too big relative to GDP and the time in the cycle – but they are not big enough to cause problems for Spain. I still cannot reconstruct the data to get construction loans that small in Spain. There are over 600 thousand homes under construction in Spain – and most of those are financed. Add the finance on those loans to other easily identifiable construction loans and you get over 10 percent of Spanish GDP. I am not confident with the Iberian Securities estimate.

However we do get clean numbers in America for BBVA’s subsidiary – and it is clear that they are into construction loans in a fairly big way – and that their construction loan book is not good and they hiding the losses.

Here is the composition of BBVA’s American lending book versus its American peer group.

Its pretty clear that BBVA USA is not afraid of construction loans relative to peers – and – on the evidence presented here – is probably rolling them (and hence deferring losses). This is nothing like the scale alleged in the Variant Perception report but it suggests that the basic Variant Perception allegation of hiding construction losses is more likely than not to be true.

I should note that the construction loans are 10.64 percent non-accrual (which is slightly less than peer). It seems unlikely you would willingly be expanding lending in this category with those credit statistics. Its far more likely that the company is hiding losses by rolling non accrual loans.

A note on scale

All these problems of the same type that Variant Perception alleges in Spain – but none are of the scale Variant Perception alleges in Spain. In other words I can unequivocally support the notion that the Spanish banks are hiding their losses – but support for the notion that these losses are so large that France and Germany will be left “holding the bag” is not to be found in the US data.

What the Spanish bankers have been telling us about their credit is – at least on the American data – easily shown to be lies. We just don’t know whether they are big lies.

For the sake of Europe I hope they are not.

John

Post script: I have linked to a few blogs here – but the important ones are Ibex Salad, and A Fistful of Euros. These blogs disagree with each other – but they are of the highest quality. If you are interested in this stuff then put them on your blog roll.

*A few disclosures are necessary here. All the key players in the blogosphere debate (hyper-bears and moderates) are my “Facebook friends”. In this day-and-age you don’t have real friends – just computer friends. I do not know what they will think of me after this post. I expect disagreement and I will post follow-ups. Some I am sure will disavow my “friendship”.

Second - at Bronte we have a small position short the Spanish banks – it has not been profitable. Moreover we are deliberately short them on the US stock exchange – which means we are short the banks long US dollars. That has been particularly bad of late because the US dollar is weak. However in a true crisis the Peseta (and yes I mean the Peseta) will be really weak – and we would rather be short them on a US listing where the cash balance is held in US dollars than on a Spanish listing where the cash balance is Euro converted into Peseta at an unfavourable exchange rate.

Just like with Charter One – BBVA caused me more than a dose of heartache. I was short Charter One when Sir Fred Goodwin and his RBS idiots came and purchased it at a massive premium. That was the single worst day of my career. Similarly I confess to being short shares in Compass when BBVA bid for them (admittedly for a much smaller premium). Nonetheless, it was – as they say – not a good day at the office.

Finally it is a long weekend public holiday in Australia. You can tell a nerd when he writes 3350 words on Spanish banking when he is meant to be on holiday.

John, this is great stuff. If you lose a few friends you will in return have gained some (I hope many) admirers. Your disclosures here are particularly good.

ReplyDeleteAs for the banks--we'll just have to wait and see. As an American, I don't hear much about this issue, and it's always good to remember that the precipitating spark of the next crisis could come out of left field.

Definitly your best post since the Swedbank one!

ReplyDeleteDon't really think you need a Spain-as-Latvia outcome to gain here; even if only scenario b) turns out to be true both the banks and the EUR should eventually get hit.

Timing remains a killer though. As long as the ECB accepts cats, dogs and office plants as collateral (and that could be a while yet) the Spain story will likely be underplayed in the markets, and that could permit the EURUSD to break 1.60 as a pure USD story before spanish flu hits the EUR. That's a lot of ground to make up.

"I have a lot of American readers whose interest in finance stops at the American border. I need to outline what is going on."

ReplyDeleteHad. You HAD a lot of american readers.

John:

ReplyDeleteThis might well be the most sophisticated post of the week in the entire blogosphere! Great analysis and a smart way to approximate their losses.

I have several indirect relatives who migrated to Spain in the early 2000's to work in construction either in semi-skilled or skilled (~site manager) trades.

Most are now back in their Balkan homelands: many small towns and villages have a tradition of having the men work elsewhere for a long time. Obviously, they came back because there was no work.

My impression, anecdotal from them and via reading, is that the construction boom was worse than what we have had here in the "sand states" because the boom was not driven by local residence buyers/speculators but by 2nd and 3rd home buyer speculators largely from the UK. These buyers vanished in an instant so that development of Euro 200K houses (that the Spanish banks financed) will not have natural buyers even in 10 years because it is located in some resort area with no real underlying economy, hence no reason for people to move there and have the income to support a house at that valuation.

The worst write-offs in the US have been on 2nd/vacation-type condos in Florida. Simply the demand is very, very flexible, hence prices can fall hard if there are no buyers. It seems to me that this was the bulk of Spain's boom. Just my 2 cents.

Great article, again.

Your analysis was very honest, and although not germane to your argument, there is the overall fact that annually 215,000 homes are sold in Spain. Today there are nearly 1.6 million homes on the market, a 7 year supply, and yet prices do not drop.

ReplyDeleteAside from your analysis, a market with such a massive overhang should reduce prices to clear the oversupply, that alone tells you that something is amiss in the Spanish housing market

Impeccable. Only criticism does not relate to financial/economic analysis and is the following: what the hell the "change in racial mix" has to do with "the large terrorist attack in Madrid" is beyond me.

ReplyDeleteI think it was AFOE which had a long piece on the Spanish market (I'm over the border in Portugal which is why I was interested).

ReplyDeleteThere's some confusion in my mond as to whether the banks are even allowed to register repossessed property at market, rather than the outstanding loan amount. Certainly, I'm told that it is very difficult indede for them to take part in a short sale of repossessed property.

If that's true, that's a horrible problem for them to have.

thanks again, mr hempton -- you continue to produce some of the best insight to be had. i've been reading edward hugh for many months in expectation of disaster in europe.

ReplyDeleteThere´s lots of money to be made here if you get it right, but it´s not gonna be easy.

ReplyDeleteIMHO the two giant spanish banks (BBVA and SAN) have been either very good or very lucky. On the international front, the fact remains that their "subprime" losses are minimal, when all their peers have had writedowns in the many billions (and there was a lot of scepticism about this at first, most analists expecting losses that never came). Domestically, they may be sheltered from the worst of the bubble because of the presence of greatest fools, the Cajas, who undertook the riskiest and crappiest loans.

To add a bit of locar colour about BBVA:

-There has been a bit of a scandal this week when it was made public that their retiring top executive pension fund allocation was more than 50 million (supposed to cover his pension based on a final salary of around 4 million).

-Of the two giants, SAN has very good relations with the government, but there is some bad blood between the very powerful Ministro de Industria, Miguel Sebastián, and BBVA´s management, who fired him from the bank some years ago.

John,

ReplyDeleteExcellent post.

With regards to the bank financing needs of Spanish constructors

A not insignificant amount of raw land is bought 'a cambio de obra'. This is to say that the vendor sells in exchange for a percentage of the final floor space - and is paid in physical apartments. In cities and towns of up to 100,000 inhabitants, these kinds of deals would be the vast majority. Even the very big builders operating in large cities were not averse to entering into this type of transaction.

Up until early 2005, builders were able to sell most of their projects from the plans and before breaking ground. The standard contract would involve 20% down on signing and another 20% linked to a milestone in the process - say the putting up of the roof. 40% in the pocket inside one year, especially if there were no immediate land purchase costs, allowed lots of them to be pretty well self-financed.

The above did not work certainly from 2006 forward, but did through 2004. Pay the architect with a flat and put another aside for the local building inspector to not notice that you're exceeding coverage and a small-time home renovator could get (temporarily) wealthy without ever going near a bank.

Ibersecurities' figures don't jive if you use American financing needs and means as a guide, but make more sense in the domestic context... although I won't swear to their veracity.

I don't know where Variant get the 470bn from. However the Bank of Spain web site has a report into Banking supervision which has some data- and I am guessing that this is their methodology. The total loans of spanish banks is 2.4tr of which 700bn is non spain lending. We know that 25% of lending in spain is either real estate development (17%)or construction (8%). 25% of 1.7 is 425bn which is pretty close to the Variant numbers. Santanders 20F says domestic lending into the real estate construction and development is €48bn, and they are supposed to be relatively underexposed relative to the cajas. So the numbers don't seem unreasonable.

ReplyDeleteBTW, Variant and Iberian Securities seem to take their numbers from the info published by the Bank of Spain. You can find the updated figures (as of Q2 2009) here:

ReplyDeletehttp://www.bde.es/webbde/es/estadis/infoest/a0418.pdf

The title is "Total credit and total dubious credit for other resident sectors (as opposed to families and ,I think, the public sector) to finance productive activities, in detail. Detailed by principal activity".

The first dataset lists gross exposure and the second "dubious" credits.

The relevant columns are numbers 4 and 15 (Construcción), and numbers 10 and 21 (Actividades Inmobiliarias).

Mr. Hempton, what, if anything, can we deduce from BBVA's acquisition of Guaranty Bank in late August?

ReplyDeleteI am Spanish, I am a banks analyst and I am positive on the two large Spanish banks (although negative on all the domestic lenders). So I started to read your comment with a certain degree of scepticism. However, I must admit, I was very positively surprised. Your comment is very good. And your attempt with the US data is original and fresh. You make a few substantial mistakes (like linking the terrorist attack with the immigration) but all those can be easily forgiven given the distance from which you write. However, I strongly disagree with your logic. I think in fact you go against one of the rules of proper syllogism-building: you go from the particular to the general – and you should not do that.

ReplyDeleteConsider this: if you find a crook in a Wal-Mart store in the middle of the Sonora Desert (assuming they do have stores there) that is overstating inventories– would you immediately short the stock assuming that the whole Wal-Mart balance sheet is a bluff? Personally, I would not.

My gut feeling: it is very possible that they are hiding bad loans in the US. This is a very recent venture and they did not have a great timing (and this is an overstatement) with the Compass purchase. But I would not assume that because of this, they are also hiding losses in Spain. They have been prudent in their lending there in the boom years (average loan-to-values in monthly origination less than 70%). And critically (VERY critically) they have a very good oversight. Bank of Spain is widely recognised as being the best banks regulator in Europe. Bank of Spain invented the anti-cyclical provisions, the same that every other Central Bank in the world is now considering adopting. I have had the opportunity to work with the Bank of Spain in a previous job. When a Bank of Spain inspector goes to one of the banks to discuss provisions (and they do that very frequently), the Head of Risk normally wets his bed the night before. They do it case by case. They sometimes “suggest” the banks the adequate level of provisions… It is not easy (and very risk) to lie to Bank of Spain. And Bank of Spain regulations explicitly forbid rolling over past-due loans, except in very limited situations. Is that the case in the US? (I am asking… I honestly don’t know).

Unless you really want to believe that there is a conspiracy here and Bank of Spain is helping them hide their losses. I am not sure you want to go down the conspiracy route here…and you are of course totally free to do so. Personally, when I feel I want to have a nice conspiracy conversation I prefer to talk about UFOs, did we really land in the moon, etc.

Regarding losses I am more negative than the other broker you mention… I assume 20% default on all developer loans and 50-60% Loss Given Default – so I forecast all developer loans to lead to more than 1,100bps of charge-offs. I do the same (even worse) with all consumer credit in Spain. I have that in my forecasts. I forecast more than 25bn of loan losses in the SAN PL for 2009 and 2010 combined. And I still have SAN generating the fourth highest RoRWA and ROE of Europe by 2010. And for 2011, when loan losses start to abate, the bottom line will, quite simply, fly.

I have been looking at Spanish banks for the best part of the last 20 years. I could go on and on… but I will leave it here. All said, I think you are very right: it is very possible that these banks (as every bank in Europe, by the way) is being “a bit creative” with their past-due classifications these days… but the problem is very unlikely to have a dramatic ending. My honest advice: you can short BBVA a bit, make a few % points here and there… but don’t get too carried away with that position. And don’t even think about shorting SAN…

As far as Variant, I really wonder why we are wasting so much time with them. In my view they are a very fine example of a time-honoured strategy: “nobody knows us, nobody cares about us, nobody reads us… so let’s make sure we say something REALLY horrible… and let’s pay ourselves a good kicker by year end”.

Go to

ReplyDeletehttp://fistfulofeuros.net/

For informed and timely opinions. This is not news and on the lightweight side.

Disappointed.

Spain is close to complete meltdown. Massive office complexes and entire residential developments stand empty. Small buinesses are closing at an accelerating rate. It is rumoured that the banks are buying back hopeless developments prior to foreclosure. They are refusing to discount the price so as to avoid booking a loss - but they are offering very aggresive financing terms - EUROBOR plus virtually nothing and often throwing in a free car.

ReplyDeleteThis has only limited success because a lot of Brits are offering fire sale prices in their rush to get back to the Motherland and avoid foreclosure there. We currently have 1.6 million empty housing units, building has slowed but not stopped, so this number will get bigger.

At some point prices must fall (currently only down about 10% from peak), and when that happens look for Banco Santander and a range of Cajas to get wiped out.

What holds Spain together is the still strong family structure. This is absorbing a lot of the pain.

Given the state of the country pretty much everything is way too expensive - something must give. Spain cannot save itself.

Thanks for the post John, very interesting and helpful. I know well what you're writing about as I'm Spanish and work closely with some of these banks. Believe me this is nowhere near the end. There is a feeling of complacency amongst them which is most worrying in my view.

ReplyDeleteBanks know no one will make them take their losses as it's too painful politically, economically and socially. Kicking the can forwards won't work forever in Spain. Japanese banks thought it would work. A few years later they realized they were wrong.

Thank you John for very enjoying reading. Also thanks for very interesting and serious comments.

ReplyDeleteI have no insight in Spanish banks, but have some general comments.

Residential mortgages in general are extremly resilient in the EU, because, we cannot walk away, and many of us have variable rates.

Today many pay just 1-2% in interest on their mortgage, which helps a lot.

Also common is to halt amortization temporarily.

Even if prices go down significantly, I don't see it lead to massive losses for Spanish banks.

Commercial Real Estate is usually the bigger problem in the EU, but I don't know so much about that.

I know it sounds terrifying, with millions of homes underwater, but noone could walk away.

This makes many just sit it out, even if it takes 5 years.

Don't know if this could explain part of the observed low defaults, and increased lending.

Ergien

Just a quick comment to add with respect to Construction loan practices in the US. Typically a construction loan has interest reserves as a part of the loan. This is a reasonable practice as a partially constructed office building won't throw off cash flow to pay loan interest. However, in instances where the economy stops dead, the practice makes these loans perform until the interest reserves are fully utilized. If a bank has substantial new construction lending, large losses can appear suddenly simply by the nature of the contracts.

ReplyDeleteClear and to the point. A great read!

ReplyDeleteAnonymous @ 5:22 AM.

ReplyDeleteYou mentioned 70% LTV loans as proof of good lending habits. However you did not address how the Value is determined. Spain has the same number of unsold homes as the US with one sixth the population and a much higher unemployment rate. Most of the homes are in the Southern resort areas. Who is going to buy them when there are so many questions about the value of the homes?

Why is it that the home prices in similar areas like Florida have crashed while the prices at which the properties are being marked are within 10% of the peak? I do realize that there are differences in mortgages and laws which makes it harder for people to walk away from homes they occupy. But what about the overhang of unoccupied and unsold homes. How do you assign a value to them when there is no market?

I posted this comment on IBEX Salad. I have not been very nice with your views, so I guess it's only fair that I include the comment here. Regards---

ReplyDeleteDisappointing. Rather, VERY disappointing.

I read your posts every now and then. I am particularly interested in those with a counterpoint on Edwards Hugh’s views. I believe Edward sometimes goes a bit too far.

I am a professional investor, so I am very familiar with Variant’s report, with the reply from Iberian securities, with Credit Suisse (bearish) reports on the Spanish financial system, with Acuña y Asociados real estate sector analysis, with the numbers from the BoS, with banks and cajas financial staments and so on and so forth, you name it, most likely I have read and digested it. I am obviously Spanish and, unfortunately, I do share a high degree of negativity with many of the bearish analyst, supported by tons of personal anecdotal evidence. I am very hungry for any challenging views in other direction… so far, not much success.

Anyway, “disappointing” was my point. You refer in this post to a report written from Australia. That is a good idea, unbiased eyes can always add something to the salad, and if distance gives you perspective, we can hardly find anyone with a farther sit. However, besides mentioning your blog and voting in your favor in your bullish campaign… what else is that comment adding? In my opinion is not only superficial, but also inaccurate, and shows a lack of understanding of the problem that is well too obvious for anyone with a minimum knowledge of the issues at hand. I am not talking about being naïve; I am talking about lack of intellectual rigour and, excuse my lack of correctness, plain ignorance.

A few comments:

- The author makes the following hypothesis: “…Spain looks solvent despite its apparent economic catastrophe. Part of the explanation might be that the economic problems in Spain fall mainly the newer immigrants and the unskilled end of the labour market – and that these people are not the loan customers of the banks…”. Ok, a hypothesis, why not… but now you have to take the additional steps to support your thinking…How do you reconcile this hypothesis with the general nasty macroeconomic figures? Or an even simpler question, what %, of the 20% unemployed, are Spanish nationals as opposed to simply residents? What is the level of debt in the hands of Spanish residents, not nationals?

- OK, we forget about that hypothesis. Let’s go for the analysis of the banks financial statements. First, real gross mistake, try to generalize any analysis on Santander and BBVA to the whole Spanish financial system… this is a very weak starting point… my excuses for stating the obvious: but these two are large international commercial banks, … what about the cajas or the medium size local banks?

- The third mistake is to assume the behavior of any institution is the same regardless of the jurisdiction. The incentives and objectives of BBVA in the US are not necessarily the same as those the bank has in Spain. I would say they are totally different, and hence its behavior with regards to financial accounting. Having said that, the analysis on Compass is original, this is the only good of the post.

- Finally, again really gross, the sizing of the problem. The guy questions the level of credit assets in the system related to developers and building companies. I am afraid this cannot be questioned; the figure comes from the regulator (Bank of Spain), as anybody with a little knowledge knows. And yes, it is staggering, it is more than 450bn EUR, almost 50% GDP. Then the author takes information from an analyst and confuses NPL and potential losses with the size of credit assets and is unable to reconcile anything (of course, how could he).

Anyway, enough said. Disappointing that you have to refer to such low quality post to support your views.

Best regards,---

I do not believe I have seen the Aussie Dollar move that much, that quickly in a long time

ReplyDeleteJohn, You described Ed Hugh as an "economics professor." Really? Where?? Hugh is not an economist (has no graduate degrees in economics), so it would be interesting to know who might hire him as a professor.

ReplyDeleteGiven Hugh's lack of academic qualifications, or vocational experience, you exaggerate (unintentionally, I'm sure) his qualifications.

Interesting analysis..

ReplyDeleteSome problems with the Compass analysis bothered me:

1) you use the $ value of construction loan book to suggest Compass is growing this portion of the loan book; and yet in the loan mix click-out you see this loan category is actually shrinking as a % of the total loan book, but you do not point this fact out. Seems to render the conclusion here mixed.

2) perhaps your most damning critique on the balance sheet is the 5-year growth rate of some of these loan categories, yet if you look at the growth in the balance sheet from 2006 to 2007, it seems exceedingly clear that an acquisition must have taken place - growth like that just doesn't happen in one year without an acquisition. Taking a growth rate from that point in time to the most recent data set would have been far more appropriate but would have taken some work and wouldn't have been nearly as supportive to the conclusion.

I think these points are crucial in that you're using them to then turn around and draw conclusions on the Spanish operations.

I'm neither long or short either of these institutions. I do appreciate the discussion though.

I live in Birmingham and am involved in banking. I am not sure about your theory that Compass is "hiding losses." They have always been a very conservative lender and the marjority of their lending is in Texas, which remains a strong market. Compass remains very active in renewing good loans and going after good business on good terms. I have not seen any bad behavior or practices from them (I have from most everyone else).

ReplyDeleteJohn, unlike many commenters here I don't think this was your finest article. I say the approach is refreshingly novel, but has the logical falacity to transfer the conclusion from the US daughter to the Spanish parent and from there to the whole Spanish system. Further problem is, that while your internal EU explanations sounds plausible, they are not rooted to deeply in reality. I would take the criticism offered by the Spanish commenters seriously.

ReplyDeleteFirst of all, migration does happen in the EU. It is very simple if

a) you are super qualified and work an English speaking job

b) you are a construction or field worker in one of the poorer countries like Greece, Portugal or Bulgaria

c) you are a German, Scandinavian or UK retiree and want to spend your time in the south

You claim the 20 percent unemployed are migrants, but as far as I know the Bulgarians are back home. They often enough did just seasonal jobs, as the family stayed behind. (And family is big there.)

From a vacation there 2.5 years ago I agree that the bubble in Spain was as big as the bubble in California. Prices per square meter at peak were about the same (but smaller units). Notice that Spaniards are much poorer than Californians on average and have signed fully recourse loans. What (I get from Ed) is saving them right now are variable interest rate loans. Which means the banks don't have the same funding advantage as the banks in the US (borrow short, go long).

But the interesting part for me is what will happen once CPI goes up in Germany. What will the Bundesbank, I mean ECB, in Frankfurt do? They will raise interest rates for sure or be hanged by the mob. But I am thinking maybe Angela has a backroom deal with the Spaniards and keeps them afloat. That puts me into your camp c) and if there

is no deal, camp d).

I just went short the Ibex-35 for lack of ideas on single spanish stocks to short, so I was hopeful to get a good SAN and BBVA dark side from John, since I owe him a couple of excellent long calls on BAC and FME

ReplyDeleteI am Italian and I think though the Spanish analist "anynomous" is right in noting that unlike the FED here in Europe expecially in more traditional countries the Central Bank was really inspecting provisions and the kind of mortgages and loans created and therefore SAN and BBVA probably were much more wild in the USA and you cannot extrapolate

Bank of Spain is better than the FED, but I know that also Bank of Italy did not let banks do crazy mortgages and I think also for construction loans they were more conservative here in southern europe and France for instance, anglo-saxons do not realize how far they have gone and luckily in Europe we did not follow them, except for Eastern europe loans.

There is an element of corruption in what happened in the US that amazingly enough this time around has exceeded by far the european standards, even in "latino" countries as far as central banking is concerned (politics is different)

I love to point out corruption and scandals around here, do not get me wrong, but US based or focused people now do not realize how bad has became for corruption and collusion in the UK and US (I lived in the US 8 years) and assume the same in Europe. Spanish banks in the US probably did things that at home are afraid to do, for some reasons Central Banks are the only decent euro institution left

If any of you sharp spanish commentars I just read above feel giving some other short ideas...unfortunately I feel that Spain could be a the dark side bet

----

"Several countries have histories of nasty endemic racism" ?? ...the nazi did not have much to do with the credit bubble...on the other hand the subprime collapse has a lot to do with the racial pandering to minorites in the US, 60% of defaults are from immigrants in Fl NE CA AZ...

Although not pertinent to your story here on BBVA and SAN, I would suggest you bookmark Wikileaks.

ReplyDeletehttp://wikileaks.org/wiki/Wikileaks

It will become useful sooner than later, I am sure.

Hi Jhon,

ReplyDeleteYou’re talking about Spanish Banks but only focusing on BBVA. The really giant Spanish bank is Santander and I’m wandering how could Santander convinced the market that they are avoiding the crisis. Santander has also American operations with Sovering. What do you think about them?

Great article. Regarding shorting, I personally feel that you have a lot of guts going short in a rampaging bull market. I also think that while overall market sentiment is positive, BBVA can raise capital at a reasonable share price (compared to what you might value BBVA at) and keep the illusion going for many years. You are probably right, but timing may be wrong. (then again you will kick yourself if this one suddenly goes into governorship of some sort).

ReplyDeleteI personally think that a downturn in market sentiment may well be needed to skin this one alive.

Maybe indicators of possible catalysts of an SP collapse will be some spikes again in the TED Spread. Does Spain have any trucking/train cartage volume statistics (year on year) to give an early idea of consumer and industrial activity.

Also I might be maintaining a log of Spanish gov't borrowing spreads against any commercial paper from Santander and BBVA as a possible indicator of a catalyst. Bond markets seem to be effected before the equity markets.

Good luck and may you profit

I will tell all of you what the banks in Spain are doing (all of them, although in larger proportion the Cajas):

ReplyDelete- They have a mortagage with an inmigrant of let say 150k on a property that it was acquired 2 years ago for 160k (so intially with a LTV of nearly 100%).

- The borrower have lost his/her job now and the ban realizes that they are or they are nearly to be in default...

- In top of that they know that property is unselleable in the market for 2 reasons: (i) the property worth today 100-110k max and (ii) it is only selleable to inmigrant and most of them are either unemployed or moving back to their countries so in fact there is not and there will not be any markt for this property so let say the value of the property will go to levels of 75k or so (50% implied loss on money borrowed)

- They are going to the clients and saying: hey, why dont u sell the property to me for the face amount of the property and your remain in the property as a tentant paying me 70% of what you are paying me for the as a mortgage.

- The inmigrant is attracted because (i) reduces their bill by 30%, (ii) reduce their risk, because they are not anymore liable for the face value of the loan as the settle the loan and become free to go back to their countries if things get worse in the comming years with no past liability. The bank is happy because (i) the loan never goes into defualt as they buy back the property, (ii) they incentivize the new tenant fromer borrower to remain in the country paying and (iii) they have some cash flow in a property that in the contrary will be very difficult to extract anything from it as no one will buy it and second, because the flow of inmigrants is now negative and the ones staying are unmeployed no one will rent it...

- BUT the simple math on it is that the bank is puting on their balance sheet a property worth 80-100k for the value of the loan (150k) so in reality with a premium of 50% and with a very reduced ROA as they are renting it for nearly nothing....

- The day, they will have to properly value all this Real estate they are buying obliged due to the circunstances (and here is the key as the BoS is not putting to much pressure on the value of the real estate asset), their asset value in RE will go down by 30% at least and please, you can tell me how this will affect their balance sheet.....EASY, they will be done !! (in the negative way).

The cajas_de_ahorro represent 60% of the Spanish banking system

ReplyDeletegoogle traductor

"Within six months, the first financial institution operated by the Government has doubled its default rate. In the first half of the year, the arrears stood at 17.3%, compared to 9.3% in December 2008, as reported by the Caja Castilla-La Mancha (CCM) in a note sent to the National Commission Securities Market (CNMV).

Thus, doubtful assets were transferred from the 1.848 million euros in December, up to 3.492 million.

According to the box, this increase is due to the increase in doubtful loans of companies in insolvency proceedings and unpaid transactions.

Regarding the consolidated result, CCM has recorded a loss of 139.36 million euros to June, compared to earnings of 25.7 million in the same period in 2008.

The company was tapped in late March by the Bank of Spain, forcing the government to approve a decree law to substantiate 9,000 billion rescue of CCM."

http://www.elmundo.es/mundodinero/2009/10/08/economia/1254987310.html

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BztBVmrAYnw

ReplyDeleteJohn

ReplyDeleteMy two cent anecdote: Back in the mid-90s Japan, as you might recall, Olympus was rumoured to be the ignominimous owner of enormous zaitech losses. After digging, I knew with some higher certainty because (purely by coincidence) I discovered I was friends with the guy who structured many of their repair bonds, (and was privvy to the ones he didn't win). The crater that realization would have blown into their balance sheet, would, if not have been terminal to the company, would likely have caused massive dilution to prevailing equity holders as the company would have been forced to raise new equity at highly distressed levels. I was short, before the info, but leant on it to maintain positions despite the stocks resiliency. The company vehemently denied their existence, and never (as far as I know) publicly acknowledged them, choosing instead to amortize the losses over the ensuing decade. Digital photography, and medical imaging subsequently grew their cash flows (and earnings) despite the hefty anchor of the amortizations of hidden losses. I got puked out of my shorts eventually, despite being right and on this rare occasion, possessing what was a material non-public edge. Go figure...

I've little doubt that where there is smoke, there proverbial fire. Too many people are privileged to such information for it to remain secret, which is why I believe the PPT is closer to the The Yeti and Area51 than flesh&blood market-puppeteer. For what it's worth, I think it's all macro now, and as events evolve, like the Japanese banks before, there comes a point where all denial is futile....

-C-

Great article and great analysis.

ReplyDeleteI am spanish an client of BBVA since I was child. My family savings are there and I am always attended by the private banking officers. I remember that last time I was in their office (well before summer since I live abroad now) I got a bit scared. In the screen of the computer they had what it seem to be some kind of reminder or training for staff (they did not show me and tried to hide it when they realize I was reading). The slogan was "Delinquencies not ´managed´go directly to the balance as loss". a clear scheme explained the process and encouraged the staff to take quick action with delinquencies to avoid they went ot the balance sheet of the bank. I quickly understood what the bank was meaning by ´managing´delinquencies. It is clear that it means to roll the loan. YES, there is a policy to hide losses implemented in BBVA (and in Santander and the Cajas too, I guess)from the bottom (staff in the offices)to the top (accounting)in Spain. The extend of it, as you say, no body knows. But, would you trust a proven liar?

As I look out of my window there are empty flats everywhere, most of them empty for the past 2 years. Something is happening here on a huge scale, I am with Edward Hugh on this one. This is big!!!

ReplyDeleteEd Hugh is good but i think he is too bearish. Somewhere between there are Ibex Salad is the truth.

ReplyDeleteAnecdotally there is much more interest in Spanish property now that UK and Germany are coming out of recession little by little and a fantastic report on Google searches last week by Justin Aldridge from Eye on Span suggests the residential Spanish sector is bouncing back well now cf last year an 2007.

Disclosure: I am an estate agent in Spain and that is where i get the anecdotal evidence from

John, I live in Spain and whilst no financial or banking expert, I am able to apply common sense to the world around me. It is definitely scenarios b, c or d - and there is huge incentive for senior managers of the banks to "smoothe" the picture of their situations. This is great research and insight and I am now a follower.

ReplyDeleteDon't really think you need a Spain-as-Latvia outcome to gain here; even if only scenario b) turns out to be true both the banks and the EUR should eventually get hit.a

ReplyDeleteI been browsing through different sites each day and yours is an interesting one. We may differ in beliefs and interest but I surely could relate in your way of writing. I’m looking forward to read and as well as share some knowledgeable information with you soon.

ReplyDeleteOne thing is totally undeniable: Spain is in a mess now. Now that three years has passed country has finally became broke. I do not know whether it was hiding its losses before, it does not matter now. You know what scares me the most is the fact that America might actually repeat same mistakes. Look at our country these days: people can’t stay away from services like PaydayLoans@ and similar, their credit cards are empty or even worse: overdraft. Do not know what Spain should expect in the nearest future, but it is a long pass to take until things go back to normal. Thanx for the post

ReplyDelete