Whether the Spanish banks are hiding their losses is a major debate going on in the blogosphere and has been detailed at length in the Financial Times. The stakes are very high – this is a debate about the stability of the Eurozone and possibly of Europe itself.

Background

I have a lot of American readers whose interest in finance stops at the American border. I need to outline what is going on.

Spain had a monstrous building boom – a building boom on (at least) Californian standards based very much on coastal development. The building boom has slowed considerably. The building boom attracted relatively unskilled labour – as building booms are apt to do – and about 40 percent of all migrants to EU settled in Spain. Wikipedia (I wish I could read the original Spanish source) state that the foreign population in Spain has gone from about half a percent of the population in 1981 to over 11 percent recently. This change in racial mix has resulted in only minor tensions (with the possible exception of the large terrorist attack in Madrid).

The financial crisis has hit Spain hard. Unemployment is about 20 percent – though this overstates the GDP contraction. A lot of the new immigrants are now unemployed.

Twenty percent unemployment would normally result in large bank losses – indeed you would expect bank insolvencies. However this has not happened. The two giant Spanish banks (Santander and BBVA) appear amongst the most profitable in the world and have substantial market capitalisation. Strangely Spain looks solvent despite its apparent economic catastrophe. Part of the explanation might be that the economic problems in Spain fall mainly on the newer immigrants and the unskilled end of the labour market – and that these people are not the loan customers of the bank. In this formulation the Spanish recession is about the same depth as the American recession – and the 20 percent unemployment rate is just an artefact of the migrant economy.

Either way both big banks are depleting loan reserves (at least compared to delinquency and non-performing loans). But both banks are reporting low losses and low loan arrears.

The banks however could be lying.

The stakes are enormous. The bears (led by Spanish resident Economics Professor Ed Hugh and the financial research house Variant Perception) argue that the Spanish regulators and banks are conspiring to hide Spain’s insolvency – and when Spain turns out like Argentina either the European central bank (that is the old German central bank) will bail out Spain at great cost to the Central Europeans or the European monetary experiment – and possibly the whole European political experiment will be challenged as Spain fails economically and socially. It’s alright to bail out Latvia after its economic disaster. Latvia is small. Spain however is large and important in a European context. Ed Hugh would argue that it is best to deal with the problem now – because delayed it will get much worse.

Do not for a minute think that the stakes here are overstated. Full blown economic collapses (eg Latvia, Iceland, Argentina) usually lead to riots and governments falling. Where ethnic tensions run high those riots often have a racial element (rioting crowds find scapegoats). Europe can paper over the Bronze Solider riots in Estonia (which pre-date the crisis). They can paper over riots in Iceland and Latvia because the economies are small. But an economic disaster in Spain would pose major difficulties – difficulties I think European Union would survive – but which would stress the system to its core.

To be this bad though the banks would need to be hiding their losses on a grand scale. Most banks in crises hide a few losses (and spread them over time). However the bears are truly apocalyptic. The Variant Perception report is an absolute classic of hyper-bearishness. If it really is that bad then either central European taxpayers are going to be stuck with a huge bill or the core political union in Europe is vulnerable.

Less worried folk have pointed to inconsistencies in both Ed Hugh and Variant Perception’s data analysis. An ordinary level bank failure could be dealt with by Central European taxpayers with only minor stress – however if you believe Variant Perception we are not looking at an ordinary level collapse – its way bigger than that. Ibex Salad – a blog with the unlikely topics of the Spanish Stock Market, Spanish Economy and the olive oil business is the counterpoint to Ed Hugh and Variant Perception.

The data is mostly ambiguous – as the bears would argue – the data is largely faked anyway – finding inconsistencies in the data is to be expected. They would argue that common sense – and the overbuild visible when you open your eyes – indicates that there is a serious problem here.

I really do not know. I am not close enough to the ground in Spain to know – and – frankly – analysing (supposedly) faked data in a language I can’t read from a desk in Australia is unusually difficult. But there seem to be four variants.

(a). The Spanish banks are telling the truth – and this is a storm in a teacup,

(b). The Spanish banks are doing a normal amount of bank over-optimism in the face of a crisis – and whilst the banks are really stretched (but not telling us) the banks are ultimately solvent – and the European experiment is fine,

(c). The Spanish banks are in fact diabolical – and the losses are maybe 15-20 percent of a year of Spanish GDP – in which case a bailout by (effectively) German taxpayers is possible or

(d). Variant Perception is in fact unreasonably bullish – and Spain will collapse economically and socially and we will be thankful if all we get back is someone like the Generalissimo. The modern European experiment will be deemed to fail because a single European Union with a single currency can’t hold together in a crisis because Germany won’t or can’t bail out Spain, Italy and Greece in a crisis.

Instinctively I am in camp (b) above. However I acknowledge all of the above are possibilities.

Migration, racism and currency union

I am going to do a little further explaining of the stakes here. The threat to currency union in Europe always was ultimately racism.

When you have currency union you can no longer have a high interest rate in Spain or Italy (when those economies warrant a high rate) and have a low rate in Germany when Germany is recessed. You have a single interest rate across the currency zone.

The underlying state of most of the past 15 years was Spain booming, Germany mildly recessed. Currency shifts or shifts in value between the Deutsche Mark and the Peseta can – by dint of currency union – no longer happen. The main mechanism of economic adjustment is removed.

America has always done that. The same interest rate applies in the rust belt, in the sun belt, in California and in Boston. And we know how economic adjustment happens. Americans move. A vast number of Americans do not live in their home town and the bulk of the world’s busiest airports are American. Internal American migration is massive.

However migration within Europe has always involved more issues. The languages are different. Several countries have histories of nasty endemic racism. There are large cultural barriers.

Monetary Union – whether by design or just outcome was always going to confront those barriers. And it was always going to be slow. There is a reason why the German/Spanish imbalance was so long lasting last decade – which was that it is much harder for a German to move to Spain than it is for say a Hoosier to move to California.

The changing racial mix of Spain throughout the boom seemed to show that massive shifts in racial mix and massive internal migration could be accommodated without the tensions of Europe’s dark past. They were the embodiment and a proof of the European political experiment. If Spain collapses beyond bail-out (as per Argentina) then monetary union is over – and economic union with racial harmony will be challenged.

As I said – the stability of Spain is a big issue and the crux point is the losses in the Spanish banking system.

The Spanish American data

Sitting at my desk in Bondi Australia I have no real advantage in answering the big questions about the solvency of Spain and whether Spain really is the black hole in Europe’s balance sheet.

But I can add to the debate. The Spanish banks have American operations – and using reasonable comparisons we can work out whether the Spanish banks are hiding their American losses. So far I have not seen any analyst do this – but it is surely worthwhile. I am going to focus on BBVA because I once had a detailed understanding of their American operation (Compass).

Several years ago BBVA paid a premium to buy Compass to form BBVA Compass.* This is how they describe the bank:

BBVA Compass is a leading U.S. banking franchise located in the Sunbelt region. BBVA Compass is among the top 25 largest banks in the U.S. based on deposit market share and ranks as the third largest bank in Alabama and the fourth largest bank in Texas. Headquartered in Birmingham, Alabama, it operates 579 branches throughout Texas, Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Colorado and New Mexico

This bank files US statutory filings (better known as “call reports”). There is no reason to presume that the Spanish regulator is conspiring with American regulators to fake the accounts of a bank headquartered in Alabama. Moreover there are other sunbelt banks to use as comparisons – whereas in Spain you can only really compare BBVA to Santander – and the bears would argue that there is no point checking for faked data by comparing it to other faked data.

If BBVA is telling the truth in America then there is a reasonable chance they have a culture of truth telling. That would suggest that they are probably telling the truth in Spain.

However if BBVA’s American accounts are riddled with deception (or at least an overly-optimistic prediction as to their losses) then it is likely that BBVA has a culture of understating losses – and that that culture extends home to Spain.

Of course the truth could be (and I would normally expect the truth to be) somewhere in the middle. A little bit of excessive optimism is normal behaviour for a banker in a crisis. But a little bit of excessive optimism does not imply bank or national insolvency – just some difficulty. The European experiment can survive that.

So what does the BBVA Compass call report say? Is BBVA hiding its American losses? If so – how bad loss hiding culture.

I have posted the key Call Report to Scribd.

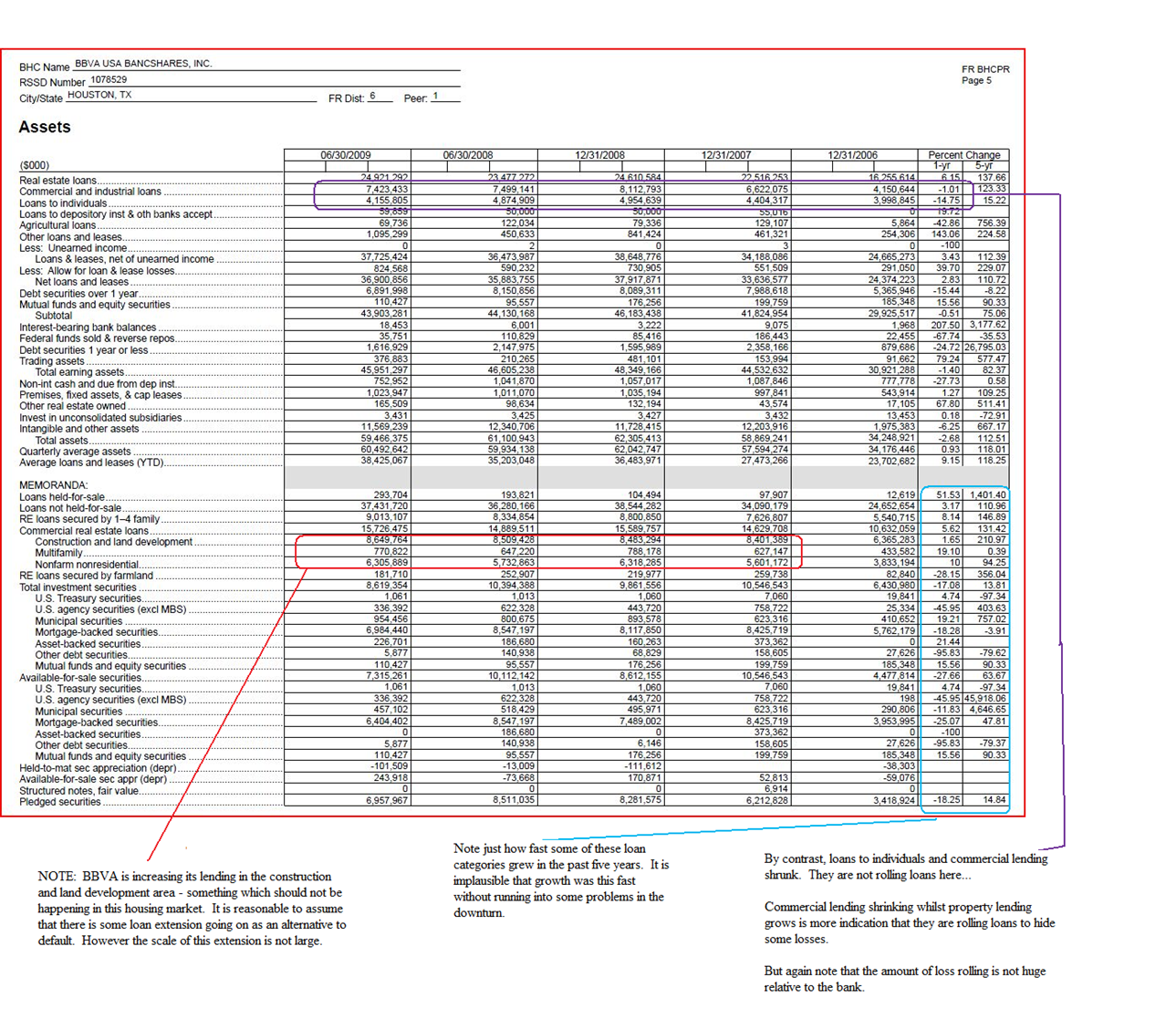

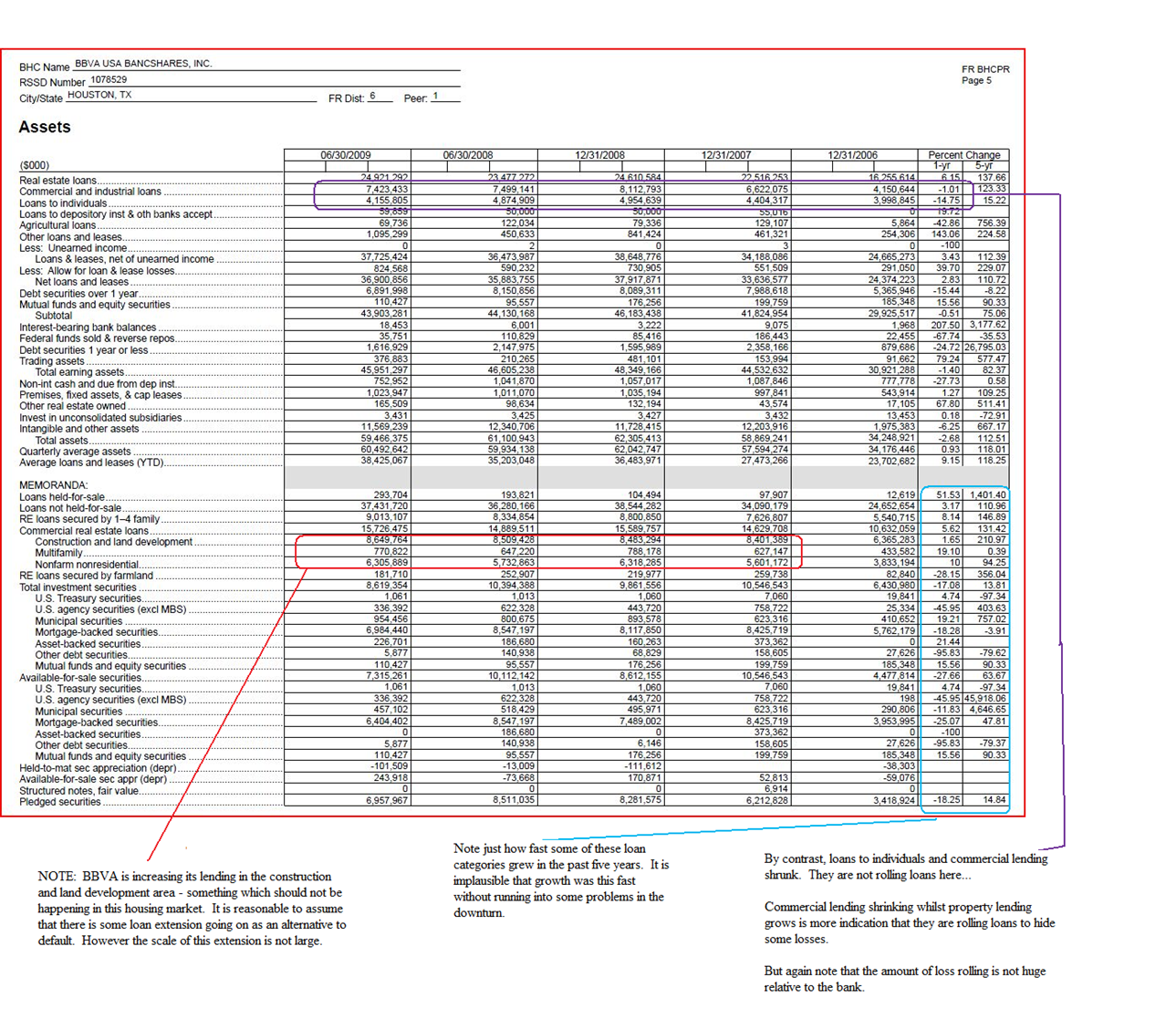

Here is a a comparison – comparing BBVA USA ratios to a sample of similar bank holding companies chosen by the FFIEC. (You will need to click for the complete picture with all three tables in this post.)

The instant conclusion is that BBVA has higher delinquencies than the competition but has lower loan loss provisions and is charging less off than the competition. This conclusion is robust almost no matter how you cut the BBVA USA data. I think we can safely conclude that BBVA is hiding its losses. If anything it is slightly worse than the above indicates because nobody in their right mind thinks that the comparables (larger American regional bank holding companies) are honestly stating their losses. But if the comparables are understating losses then BBVA is understating them more.

This puts me firmly into camps (b), (c) or (d) above. The question is no longer whether they are hiding the losses – but whether the scale of problems (in Spain) is sufficient to cause major political ructions or whether it is just an issue for the stock market. [Disclosure: I am short BBVA and the position is modestly painful as the stocks have appreciated.]

How are BBVA hiding their losses in America?

There is a time honoured way of hiding losses in banking – a method that Variant Perception suggests is being done on a breathtaking scale in Spain. The method is rather than call a bad loan bad – to just extend it a bit more credit. If the borrower can’t pay the interest give them a bigger loan or line of credit. They will use the loan to become current. The slogan is that a “rolling loan gathers no loss”. Even the most diabolical subprime mortgage book in the US showed only small losses until the market stopped rolling the loans.

We have some evidence that BBVA is rolling bad loans. Here is the loans outstanding by sector (again you will need to click for detail):

The level of rolling loans is not at the alarming levels that Variant Perception alleges are present in the Spanish economy. Then again Alabama and the other states in which Compass is large do not have 20 percent unemployment. The aggression which BBVA grew the book in the past five years however is breathtaking. You can see where all that Spanish risk comes from and why Spain had such a monstrous property boom.

Construction loans – a perspective from the American book…

The main allegation in the Variant Perception report is that the Spanish banks are massively overweight construction loans – and that they are extending those loans rather than allowing default. The core statistic is given in the following paragraph:

Consider this: the value of outstanding loans to Spanish developers has gone from just €33.5 billion in 2000 to €318 billion in 2008, a rise of 850% in 8 years. If you add in construction sector debts, the overall value of outstanding loans to developers and construction companies rises to €470 billion. That's almost 50% of Spanish GDP.

They add that they think that most of those loans will go bad (which implies a Spanish crisis many times worse than America – and implied bailout requirements that are similarly bad).

Construction loans at almost 50 percent of GDP is a truly astonishing figure. The entire US mortgage market is roughly 10.4 trillion dollars – or about 75 percent of GDP (and as the crisis has shown that seems too large). The idea that construction loans are nearly 50 percent of GDP had me falling off my chair. I tried to confirm this figure (as it felt like garbage). Alas I could not. However Iberian Securities has done some legwork:

Variant picks-up a classic wild-card to spice-up the report. Specifically, they say most of the €470bn in outstanding loans to developers/construction (50% of Spain’s GDP) could go bad. The report forgets to mention- however- that a chunk of the €32 bn in outstanding loans to developers does not necessarily involve residential lending but commercial lending (which is relatively safe in Spain , in our view). It does not say either that a not-low percentage of construction activity in Spain involves public works, so a proportion of the construction-related debt (€141bn) should be attached to that public sector accordingly. Also it is worth considering that residential work-in-progress in Spain — one of the biggest contributors to the €320bn figure — is generally collateralized (with Spanish major developers reporting LTV of 50-65% approx). Factor-in these and the final loss on this portfolio should be a fraction of what Variant claims. In our models, we assume a 15% peak NPL ratio on Developers (7.6% in 1Q09) and a 10% NPL ratio on Construction loans (6.7% in 1 09).

Even at 6.7 percent of GDP construction loans are too big relative to GDP and the time in the cycle – but they are not big enough to cause problems for Spain. I still cannot reconstruct the data to get construction loans that small in Spain. There are over 600 thousand homes under construction in Spain – and most of those are financed. Add the finance on those loans to other easily identifiable construction loans and you get over 10 percent of Spanish GDP. I am not confident with the Iberian Securities estimate.

However we do get clean numbers in America for BBVA’s subsidiary – and it is clear that they are into construction loans in a fairly big way – and that their construction loan book is not good and they hiding the losses.

Here is the composition of BBVA’s American lending book versus its American peer group.

Its pretty clear that BBVA USA is not afraid of construction loans relative to peers – and – on the evidence presented here – is probably rolling them (and hence deferring losses). This is nothing like the scale alleged in the Variant Perception report but it suggests that the basic Variant Perception allegation of hiding construction losses is more likely than not to be true.

I should note that the construction loans are 10.64 percent non-accrual (which is slightly less than peer). It seems unlikely you would willingly be expanding lending in this category with those credit statistics. Its far more likely that the company is hiding losses by rolling non accrual loans.

A note on scale

All these problems of the same type that Variant Perception alleges in Spain – but none are of the scale Variant Perception alleges in Spain. In other words I can unequivocally support the notion that the Spanish banks are hiding their losses – but support for the notion that these losses are so large that France and Germany will be left “holding the bag” is not to be found in the US data.

What the Spanish bankers have been telling us about their credit is – at least on the American data – easily shown to be lies. We just don’t know whether they are big lies.

For the sake of Europe I hope they are not.

John

Post script: I have linked to a few blogs here – but the important ones are Ibex Salad, and A Fistful of Euros. These blogs disagree with each other – but they are of the highest quality. If you are interested in this stuff then put them on your blog roll.

*A few disclosures are necessary here. All the key players in the blogosphere debate (hyper-bears and moderates) are my “Facebook friends”. In this day-and-age you don’t have real friends – just computer friends. I do not know what they will think of me after this post. I expect disagreement and I will post follow-ups. Some I am sure will disavow my “friendship”.

Second - at Bronte we have a small position short the Spanish banks – it has not been profitable. Moreover we are deliberately short them on the US stock exchange – which means we are short the banks long US dollars. That has been particularly bad of late because the US dollar is weak. However in a true crisis the Peseta (and yes I mean the Peseta) will be really weak – and we would rather be short them on a US listing where the cash balance is held in US dollars than on a Spanish listing where the cash balance is Euro converted into Peseta at an unfavourable exchange rate.

Just like with Charter One – BBVA caused me more than a dose of heartache. I was short Charter One when Sir Fred Goodwin and his RBS idiots came and purchased it at a massive premium. That was the single worst day of my career. Similarly I confess to being short shares in Compass when BBVA bid for them (admittedly for a much smaller premium). Nonetheless, it was – as they say – not a good day at the office.

Finally it is a long weekend public holiday in Australia. You can tell a nerd when he writes 3350 words on Spanish banking when he is meant to be on holiday.