This blog is reprinted on Talking Point Memo. In that format the post is unreadable unless you click the permalink. The tables are too wide – and have prompted a reformat of my home blog.

In the last post I introduced readers to cumulative default curves. In this post I am going to create a naïve (but surprisingly robust) model of end losses using those cumulative default curves. Later posts are going to detail the limitations of this model and what (if anything) allows me to attest to the model’s accuracy...

Also I am going to use only the cumulative default curves up until December 2008. There are a couple of reasons for doing this. Firstly I am lazy and at Bronte Capital we originally did this analysis in March and I can cut and paste the internal note we wrote at our fund. More pertinently though the default curve past December gets distorted by the foreclosure moratorium which meant that some individual cumulative default curves are quite kinked. For instance the sequential default for the last four quarters on the Fannie Mae 2007 vintage is 1.1 billion, 1.5 billion, 1.0 billion and 1.5 billion. If you used the 1.0 billion default recorded in the first quarter of this year you would underestimate the end defaults by presuming the foreclosure moratorium was a continuing part of the sequence and not a distorted data-point. So whilst it appears lazy to use analysis I wrote in March not updated for new results, there is some method in that.

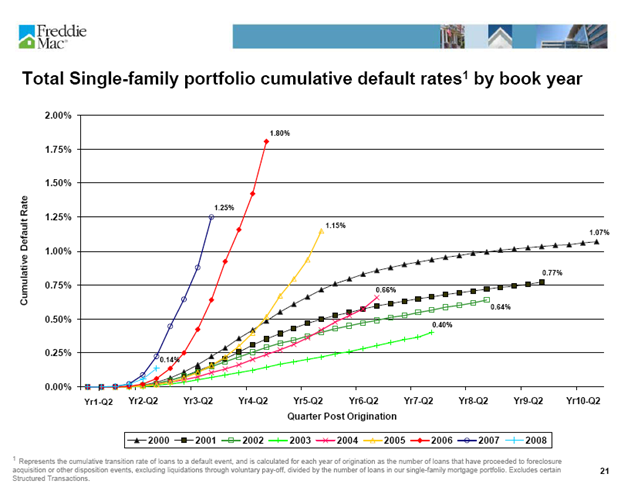

Here is the default curve – as published by Freddie Mac – until the end of 2008. This curve does not include the kinks caused by foreclosure moratoriums.

It has the usual “to the sky” character for the 2006 and 2007 books of business, however the kinks a the end of the curve are not present. (Compare to 2003 curve to the most recent 2003 curve which you can find in the last post – and which has a notable kink at the end of it.)

I would have loved the data points on this curve as actual numbers to run through the model. I wrote to Freddie Mac (and to Fannie Mae) and asked for that data and they refused to give it to me. So I did the best I could and printed the curves on graph paper and read the numbers off the graph paper. [If you are a policy analyst at the National Economic Council looking at this issue perhaps the company will give you actual data points!]

| Last six data points | cumulative default 2006 originations (bps) | cumulative default 2000 originations (bps) | Ratio of cumulative defaults 2006/2000 |

| Y3, q4 | 115 | 41 | 2.8 |

| Y3, q3 | 90 | 35 | 2.6 |

| Y3, q2 | 64 | 29 | 2.2 |

| Y3, q1 | 42 | 22 | 1.9 |

| Y3, q4 | 24 | 15 | 1.6 |

| Y2, q3 | 13 | 8 | 1.6 |

If the ratio were constant (it is not) then we would have a really good method of projection. Instead the 2006 pool is getting worse relative to the 2000 pool quarter by quarter. My guess is that the end cumulative defaults will not be 2.8 times the 2000 pool (the current ratio) but 4.5 times (substantially worse than the current ratio). This is an educated guess looking at the charts – nothing else. I have tried testing this guess with (former) senior finance execs at Fannie. They said they would like to measure they rate at which the curves are diverging (preferably by state or market character) against rates at which house prices are falling. They want to test how much of the expansion of defaults is induced by falling house prices. They are after a sounder end-default estimate.

That said – I am stuck with the educated guess made above.

| Current cumulative default (bps) | Guessed end default ratio | End cumulative default | |

| Base year 2000 | 104 | 110 | |

| 2001 | 74 | 0.8 | 88 |

| 2002 | 62 | 0.75 | 83 |

| 2003 | 32 | 0.7 | 77 |

| 2004 | 52 | 1.1 | 121 |

| 2005 | 81 | 2.5 | 275 |

| 2006 | 115 | 4.5 | 495 |

| 2007 | 63 | 6 | 660 |

| 2008 | negligible | 400 |

Obviously the big problem years are the 2005, 06, 07 and 08. Previous years have largely played out. That is to be expected because if you had a mortgage you couldn’t afford originated in 2004 then you either refinanced it in the boom into a later year or you have defaulted already. I have only guessed the end default in 2008 – there is simply not enough public data to make anything other than an informed guess – however gossip suggests that 2008 is a bad year but not as bad as 06 or 07 for defaults.

From here – with data about how many mortgages were originated each year – you should be able to work out how many defaults are yet to occur. This is done below. The originations for the years 2000-2003 are made up because I can’t find the data any more – but the action is not there anyway. What matters is the later year.

| Year | current cumulative default (bps) | end cumulative default (bps) | Defaults still to come (bps) | Originations in year (billions) | Defaults still to come (billions) |

| 2000 | 104 | 110 | 6 | 450 | 0.3 |

| 2001 | 74 | 88 | 14 | 450 | 0.6 |

| 2002 | 62 | 83 | 21 | 450 | 0.9 |

| 2003 | 32 | 77 | 45 | 450 | 2.0 |

| 2004 | 52 | 121 | 69 | 495 | 3.4 |

| 2005 | 81 | 275 | 194 | 501 | 9.7 |

| 2006 | 115 | 495 | 380 | 577 | 21.9 |

| 2007 | 63 | 660 | 597 | 460 | 27.5 |

| 2008 |

| 400 | 400 | 358 | 14.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Total defaults still to come | 80.7 | ||||

This suggests that there are almost 81 billion of mortgages in the book yet to default. This is considerably more than the cumulative defaults to date – and implies a massive increase in defaults. Whitney Tilson is right – prime mortgages owned by the GSEs are going to default in a massive way in the next couple of years.

I have done a similar analysis for Fannie Mae and I predicted that just over $125 billion of defaults were embedded in the default curves at that company.

Remember though that these are defaults, not losses. Severity is the key to the losses.

Neither company publishes severity by year of origination (something I would deeply desire). However Fannie Mae publishes its severity in each period for the whole book.

The severity at Fannie Mae was as low as 9% in 2005. I do not have an accurate table of severity by year of origination – but Fannie gives recovery data as follows (severity percentage = 1 minus recovery percentage):

| Real estate owned net sales compared with unpaid principal balances (which is one minus severity numbers)

| |

| 2005 | 93% |

| 2006 | 89% |

| 2007 | 77% |

| 2008 q1 | 74% |

| 2008 q2 | 74% |

| 2008 q3 | 70% |

| 2008 q4 | 61% |

| 2009 q1 | 57% |

| 2009 q2 | 54% |

The severity numbers at Freddie Mac are consistently a little lower than at Fannie Mae. I think the reason is that Fannie Mae did most of Countrywide’s business and there was more valuation fraud at Countrywide. If this is the case it strikes me that Fannie has a good case against Bank of America (who now own Countrywide) but they have not chosen to litigate.

Either way, severity is rising though with the recent stabilisation of REO sales prices (more evident at Freddie than Fannie) I think we can presume some stabilisation at the new (higher) severity levels. Anyway I ran the model assuming end average severities for various books of business. This produces an estimate of losses yet to come.

| Year | Defaults to come by year (billions) | Severity by year (percentage) | End losses (billions) |

| 2000 | 0.3 | 10% | 0.0 |

| 2001 | 0.6 | 12% | 0.1 |

| 2002 | 0.9 | 14% | 0.1 |

| 2003 | 2.0 | 15% | 0.3 |

| 2004 | 3.4 | 18% | 0.6 |

| 2005 | 9.7 | 40% | 3.9 |

| 2006 | 21.9 | 60% | 13.2 |

| 2007 | 27.5 | 55% | 15.1 |

| 2008 | 14.3 | 30% | 4.3 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Losses still to come | 37.6 | ||

When I originally wrote this model Freddie Mac had already provided for 15.6 billion losses yet to come. That is the provisions number at the end of 2008 in the following graph.

Given that I thought that there was $37.6 billion of losses embedded in the book I thought that Freddie was under-reserved by $22 billion. This is a big number to be sure – but in the scheme of things that are said about the losses at Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac most people (certainly most taxpayers) would be happy that the hole in Freddie Mac’s book is “only” $22 billion. [The level of under-provisioning at Fannie Mae was similar… our estimate was that neither institution posed much threat to the US Treasury.]

Since I did this estimate Freddie Mac has actually realised $2.9 billion of losses and the reserves have risen to 25.2 billion. This means that Freddie has now provided for an additional 12.5 billion dollars. The remaining hole in Freddie’s accounts is now “small” – say 7.5 billion dollars.

Plausibility check

When you estimate something in such a convoluted way it is incumbent to run a plausibility check. Look again at the losses and reserve picture for Freddie Mac.

Note that Freddie is writing off roughly 900 million per until the last quarter. The spike in the last quarter to 1.9 billion was due to the expiry of the foreclosure moratorium as well as due to the generally bad housing market. I estimated that at the end of 2008 there were 37 billion in losses left to come. Since then they have realised $2.9 billion in losses including the spike in realised losses at the end of the foreclosure moratorium. I think there are now about 34 billion in losses left to come. If the next six months is twice as bad as the last six months then we will be running off at roughly $6 billion per half or $12 billion per annum. We can cope with three years that bad without threatening my estimate. Given that the early stage delinquency of the GSEs is currently falling (see this OTC report) I think this is a reasonable (if harsh) assumption.

Plausibility summary: my loss estimates pass this plausibility check. I have run half a dozen other plausibility checks (some quite convoluted and detailed). The estimates are robust to all of them.

Summary of Part IV

In this post I show how using naïve (but surprisingly robust) models using data in the cumulative default curves you can get estimates of the end losses of both Fannie and Freddie.

Using these models I show that the end losses in the traditional guarantee book of business are very close to the reserves currently embedded in Freddie Mac’s accounts. [The same applies at Fannie Mae too.]

This argues strongly against the notion that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will be substantial ongoing drains on the Federal budget. It also argues fairly strongly against the notion that the quasi-government GSEs cost taxpayers more than the private sector companies that they competed with. AIG – who led the FM Watch – an anti-Fannie-and-Freddie lobby group will wind up costing taxpayers considerably more than the GSEs.

Moreover the losses on the GSE’s core business (the losses modelled in this post) look like they are about the same as the original GSE capital base. If the GSEs had not (foolishly) purchased private label mortgage securities (the losses detailed in Part II) then the cost to the taxpayer would have been negligible.

This has big implications for the reform of GSEs – something supposedly under discussion at the NEC – and also of concern to many. The traditional guarantee business of the GSEs simply did not perform that badly during the worst mortgage crisis in modern finance. That should be borne in mind by the GSE critics.

As to what the end cost to the government will be – and whether there is any residual value in the remaining Fannie and Freddie securities – that is the subject of a future post in this sequence.