Tuesday, March 17, 2009

Gold is very expensive

Monday, March 16, 2009

Fannie versus Freddie credit performance

Friday, March 13, 2009

Financial chauvinism

Thursday, March 12, 2009

Krugman’s illogic extended

Wednesday, March 11, 2009

Accrued interest on Voodoo maths

Paul Krugman’s false logical step

That said, some decision must be reached on bank liabilities. Sweden guaranteed all of them. If forced to say, I would go the Swedish route; but of course we can’t do that unless we’re prepared to put all troubled banks in receivership. And I’m ready to be persuaded that some debts should not be honored — this is a deeply technical question.

Tuesday, March 10, 2009

Fools seldom differ

BUFFETT: Yeah, the interesting thing is that the toxic assets [of American banks is] if they're priced at market, are probably the best assets the banks has, because those toxic assets presently are being priced based on unleveraged buyers buying a fairly speculative asset. So the returns from this market value are probably better than almost anything else, assuming they've got a market-to-market value, you know, they have the best prospects for return going forward of anything the banks own. The problems of the banks are overwhelmingly not toxic assets, you know. They may have been one or two at the top banks, but they are not going to do in--if you take those 20 banks that are subject to the stresses, they're not going to do those banks in. Those banks have the earning power which has never been better on new business going out of this to build capital positions if they pay low dividends which they're starting to do now.JOE: Hm.BUFFETT: Toxic assets really are not the problem they were. Now, when I said it was contingent--I didn't remember being exactly contingent on TARP, but it was contingent on the government jumping in.JOE: Right.BUFFETT: The government needed to act big time in September, I will tell you that.JOE: So...BUFFETT: And they did act big time.JOE: So you are OK with the shift to providing the banks with capital as opposed to the original intention of the TARP for actually getting the toxic assets off the books?BUFFETT: Yeah, and interestingly enough, they don't need to supply the banks, in my view, with lots of capital. They need to let almost all of--I mean, the right prescription with most of the banks is just let them pay very little in the way of dividends and build up capital for awhile, and they will build up a lot of capital. The government has needed to say--what the government needs to say is nobody's going to lose a dime by having their deposits in these banks. They're going to make lots of money with the deposits.JOE: Hm.BUFFETT: The spreads have never been wider. This is a great time to be in banking, you know, if you just get past the past and they are getting past the past. I mean, right now every time a loan is made to somebody to buy a house--and we're making, you know, making millions of loans--four and a half million houses will change hands this year out of a total stock of less than 80 million. So those people are making good mortgages. You want those assets on your books and you get a great spread in putting them on now. So it's a great time to be in banking, but you do have to get past this past. But the toxic assets, in my view, you know, if they've been written down to market, I'd rather buy those assets from the bank than any other assets they've got.JOE: Hm. OK...

Sunday, March 8, 2009

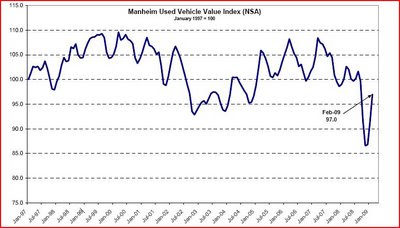

Optimism Porn – used car prices

that is great news. anyone in NY want to buy a 2003 mazda protege with 55k miles really cheap? i bought it to commute to my hedge fund job and don't need it any more.

Friday, March 6, 2009

Voodoo maths and GE

Mr. Sherin said he expects the financial services business to be profitable for the first quarter and full-year 2009, and he addressed questions on the Company’s position on cash generation and loss reserves: "Over a three-year period here, we expect GE Capital to be profitable, even after $35 billion of losses and impairments. We're looking today for GE’s total cash flow to be around $16 billion for the year. In our stress case we could be down in the $14 billion level. In either scenario, we can fund the company. If conditions were to deteriorate beyond what is in our stress scenario, we also have the option of scaling back originations in GE Capital to conserve cash and capital." Emphasis added.

General disclaimer

The content contained in this blog represents the opinions of Mr. Hempton. You should assume Mr. Hempton and his affiliates have positions in the securities discussed in this blog, and such beneficial ownership can create a conflict of interest regarding the objectivity of this blog. Statements in the blog are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to certain risks, uncertainties and other factors. Certain information in this blog concerning economic trends and performance is based on or derived from information provided by third-party sources. Mr. Hempton does not guarantee the accuracy of such information and has not independently verified the accuracy or completeness of such information or the assumptions on which such information is based. Such information may change after it is posted and Mr. Hempton is not obligated to, and may not, update it. The commentary in this blog in no way constitutes a solicitation of business, an offer of a security or a solicitation to purchase a security, or investment advice. In fact, it should not be relied upon in making investment decisions, ever. It is intended solely for the entertainment of the reader, and the author. In particular this blog is not directed for investment purposes at US Persons.